Feature Assessment: Cultural landscapes / Boundaries and patterns of enclosure

# Boundaries and patterns of enclosure

| Overall vulnerability |  |

# Feature(s) assessed:

- Dry stone walls and hedges including single walling

- Variety of wall types and wall furniture

- Boundary markers and features

- Banks, ditches and other earthworks

- Pattern of Enclosure - Smaller scale mosaic of upland farmed enclosures, lowland pastoral landscapes, open moorland, river valleys & species rich grassland

- Fossilised medieval field systems - strip fields & evidence of Medieval open field farming (South-West Peak) shape of wall, strip field pattern in modern dry stone landscape (White Peak)

- Irregular and semi-regular enclosure including prehistoric field systems

- Field pattern of enclosed in-bye land and open moorland grazing

- Enclosed farmland

- Repeating pattern and rhythm of dry stone walls

- Pattern of large square enclosure on the plateau, C18th and C19th parliamentary enclosure

- Post medieval enclosure

# Special qualities:

- Beautiful views created by contrasting landscapes and dramatic geology

- Landscapes that tell a story of thousands of years of people, farming and industry

- Characteristic settlements with strong communities and traditions

# Feature description:

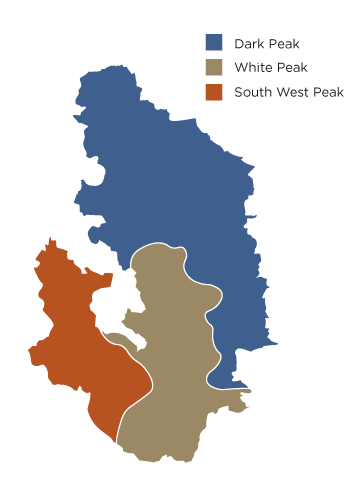

Boundaries and patterns of enclosure, including type and size, are distinctive in the different areas of the PDNP.

Both dry stones walls and hedgerows have been used to enclose land for hundreds of years. They mark the boundaries of fields across the PDNP and are a prominent feature of the landscape. Large upland areas of the Dark Peak remain open but gritstone dry stone walls are used as one way to define ownership boundaries. Dry stone walling and hedges figures for 1991 revealed 8,756 km of dry stone walls and banks and 1,710 km of hedgerows in the PDNP. Although difficult to date, some dry stone walls are believed to go back to medieval times and Romano-British foundations underlying later stone walls have been recorded. Other features used as ownership boundaries such as roads, tracks, and natural features are addressed elsewhere. See ‘Paths, tracks and trails’.

In the White Peak dry stone walls made from limestone are prevalent. Smaller, narrow fields found around villages are evidence of the earlier enclosure of strip farming. Former common land was often the focus of Parliamentary Enclosure Acts in the late 18th to early 19th century and tends to feature more regular medium to large sized fields, with much straighter boundaries. The walls themselves are built without mortar and vary in construction. The type of stone used depends on the geology of the area in which they were built with limestone, gritstone and other sandstones being used. Boundaries built using quarried stone are generally neater than those made from random stone, but both are essential components of the landscape.

Boundary markers can also include natural features such as rock outcrops or ridge lines. Other features that remain include guide stoops. Dating back hundreds of years these stone waymarkers helped travellers navigate remote routes and were placed where paths intersect, often showing the direction of the nearest market town.

Hedgerows are also an important historical feature, particularly in the White Peak and South West Peak. They tend to be in the low-lying land in areas such as the Derwent Valley or on the fringe of the Derbyshire PDNP and are predominantly blackthorn and hawthorn. In areas of the Dark Peak holly has also been used as a hedging plant.

The patterns of field enclosure provide valuable information on landscape change and historic land use, and reflect time-depth in the landscape. Medieval field strips fossilised by later walls are a characteristic feature of the White Peak landscape, but other types of enclosure pattern are equally significant. Earthworks, such as lynchets, ridge and furrow, ditches and banks also define former or current fields.

Highly significant prehistoric field systems are present in a number of areas, including open moorland and agricultural areas. These may be seen as earthworks at a completely different orientation to the current boundaries, although archaeological research shows that prehistoric field patterns can be echoed in the pattern of current boundaries, for example at Roystone Grange.

The varying patterns of enclosure that are found in the PDNP are extremely important to the character and heritage value of the PDNP landscape.

# How vulnerable are boundaries and patterns of enclosure?

Boundaries and patterns of enclosure have been rated ‘high’ on our vulnerability scale. This score is due to high sensitivity and exposure to climate change variables, coupled with an often poor general condition, and a moderate adaptive capacity.

It is difficult to ascertain the overall current condition of dry stone walls as it is varied. However the condition of hedgerows is viewed as poor. Extreme weather is one of the key potential impacts increasing deterioration and maintenance costs leading to a greater risk of abandonment. Another is changes to land use, which may mean boundaries are removed to enlarge fields. Changing farming practices such as an increase in ploughing may affect earthwork features. Walls in poor condition are also often used as a source of stone to repair other walls.

There is limited funding available to improve these features and there is currently a shortage in terms of the number of people with the necessary dry stone walling skills needed for management and maintenance. Even the repair and rebuilding of walls, whilst retaining the landscape appearance, can remove or alter historic information that is very valuable (such as the physical relationships between features, or distinctive construction styles). Planting could improve hedgerows condition by filling in gaps and diversifying species. If not designated, prehistoric field systems are vulnerable to landscape change.

# Current condition:

In many cases the condition of boundaries and patterns of enclosure vary depending on the area in which they are found. Hedgerows in the PDNP are considered to be in a generally poor condition often due to a lack of sympathetic management. Many are overgrown or have gaps, and are species-poor when compared to other areas. They are mainly made up of hawthorn and blackthorn although in some areas include holly and hazel.

Dry stone walls are in a variable condition, with many in a poor condition due to lack of maintenance, the removal of stones, or even vandalism. It is difficult to date dry-stone walls but some are believed to date back to medieval times while others are said to have Roman and prehistoric foundations. During the 1970s and 1980s, over 250 km of field boundary was lost. This occurred for a number of reasons including a need to increase entrances and gateways for larger machinery, and a trend to increase the size of fields for agricultural efficiency. Over 20 years ago it was estimated by the Countryside Commission that in the UK as a whole as many as 50% of walls were derelict. Such figures for the PDNP are not available at the time of writing.

Limited funding to rebuild damaged walls or replant hedgerows has been available from a number of countryside agencies. During the 1980s, 11 km a year were rebuilt and between 1990 and 1996 that figure rose to 30 km a year. Stone wall restoration has also been included in environmental stewardship agreements. By 2011, 442 km of restoration in the Dark Peak had been included in such agreements. Whilst there has been a rise in interest in dry stone walling, there remains a limited number of people with the necessary skills to repair, restore or rebuild these boundaries.

Although the rate of boundary repair in the PDNP is known to be increasing, many of the components that make up these landscape-scale patterns of enclosure are either in poor condition, or under threat. This threat is often from factors unrelated to climate change, such as continued agricultural improvement and the reworking of mineral resources.

# What are the potential impacts of climate change?

| Overall potential impact rating |

# Direct impacts of climate change

Both dry stone walls and hedgerows are sensitive to greater extremes of temperature as a result of climate change, and increased annual average temperatures. Hotter summers and warmer winters could lead to longer plant growth seasons. Dry stone walls could be structurally threatened by increased thermal expansion and contraction of the stone and soil and an increase in wall flora such as ivy. This may accelerate the speed of deterioration while increasing maintenance costs and the threat of abandonment. Conversely, this could create a new habitat for wildlife. Hedgerows are sensitive to changes in plant growth and shading which in turn could change the composition of understory flora and associated wildlife. Data Certainty: High

An increase in storms and extreme weather could see dry stone walls and wall furniture likely to suffer from increased weathering, while the stability of walls and boundary markers could be compromised in some areas. In hedgerows, there could be a loss of trees and other woody species due to severe drought, or the loss of mature and older standard trees due to storms creating large gaps. Prehistoric field system earthworks may also be damaged by storm events and weathering which can also have an impact on vegetation. Data Certainty: High

Drier summers and wetter winters could affect ground conditions and the stability of boundaries through an increase in the process of shrink-swell, particularly on clay soils. Data Certainty: Moderate Limestone is sensitive to chemistry changes and pollution, so an increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide could lead to further erosion of limestone features in dry-stone walls such as gateposts. A loss of lichen species – which can be used to date structures - could occur due to atmospheric pollution. Data Certainty: Moderate

Hedgerow plants and trees are sensitive to changes in rainfall, which could also risk erosion being accelerated. Drought could reduce ground cover, increasing erosion further. Decreases in summer rainfall could lead to increased mortality and die-back of certain hedgerow tree species such as beech. Drought may also increase trees’ susceptibility to pests and diseases. In addition, prolonged flooding in the growing season due to extreme weather events could see woody species at risk of dying. Wet ground conditions would make winter trimming of hedgerows more difficult and therefore it may be carried out earlier in the year – decreasing their value to wildlife as a food resource. Increased wet soil conditions could cause damage to soil structure, also leading to increased die-back of hedgerow trees. Data Certainty: Moderate

# Human behaviour change

Both hedgerows and dry stone walls are sensitive to agricultural changes on the land they bound. Wetter winters and drier summers could lead to changes in land management practices. An intensification of farming may lead to a rise in offsite impacts such as pesticide drift and nutrient enrichment. Intensification could also lead to a reduction in the use of buffer strips and margins that protect hedges. Wetter winters could also increase the need for modern barns for housing livestock, potentially altering the character of the landscape, particularly around villages associated with fossilised strip fields. Data Certainty: High

If land were to be converted to arable use, it would be likely to cause the loss of traditional landscape features including stone walls and hedges - as fields are enlarged and ploughed. There would be complete loss in some areas and the reduction of extent in others. If boundaries are removed or ploughing increased this could damage their relationship to buried archaeological remains and adversely affect prehistoric field system earthworks. There are however many other variables in addition to climate change that will influence future land use, and so confidence is low. Data Certainty: Low

Hedges are sensitive to storms and extreme conditions so it may mean they have to be managed differently, for example by planting different species, reducing their height, or removing standard trees to minimise storm damage. This could decrease their value as a resource for wildlife and as cultural heritage features. An increase in extreme events such as flooding is likely to increase economic pressure on pastoral farmers, potentially leading to some areas becoming uneconomic to farm. This could have a high impact on the maintenance of boundaries. Data Certainty: Low

The character of agricultural landscapes could be sensitive to increased demand for renewable energy sources if energy infrastructure such as wind turbines or solar panels are installed. An increased desire for trees as carbon dioxide sinks could lead to the planting of trees in hedgerow gaps or the creation of new hedgerows along field boundaries. This would improve wildlife connectivity, increase biodiversity and create habitat for nesting birds, mammals and invertebrates. However, if hedges replace walls this would lead to loss of historic landscape character. The traditional look of patterns of enclosure in the landscape could also be lost or degraded through changing farm practices - both diversification and intensification. Data Certainty: Low

# Invasive or other species interactions

Atmospheric changes coupled with increased annual average temperatures could lead to more rapid plant growth, which could accelerate damage to dry-stone walls and earthworks, for example trees growing close to the structure. Hedges may also need increased maintenance. If grazing regimes change or land is abandoned, increases in scrub growth may see the traditional look of the various patterns of enclosure degraded or even lost. Conversely, an intensification of agriculture associated with the potential for increased crop growth could also have a negative impact on these patterns. Data Certainty: Moderate

Increased annual average temperatures could see a rise in plant pathogens and higher populations of burrowing mammals such as badgers, moles and rabbits. Hedgerow plants and trees sensitive to disease could be damaged or die off, changing hedge composition and condition and possibly leading to the loss of key species. In areas with a high concentration of burrowing mammals increased damage could be caused to walls and earthworks, leading to an increased need for repair where they are destabilised. Data Certainty: Moderate

Warmer, wetter winters could see an increase in the occurrence of livestock feed crop pests, liver fluke and other livestock diseases - particularly those transferred by insects such as the bluetongue virus. Data Certainty: Moderate Factors such as these affecting the financial viability of the pastoral system could have profound impacts on the future of farming in the PDNP, and consequently reduce the need to maintain field boundaries.

# Other indirect climate change impacts

Warmer and drier conditions would affect hedgerow species such as beech, hawthorn and rowan that need a period of colder weather to ensure flower and fruit production. Any reduction could affect food sources for wildlife. Drier conditions may also mean hedgerows are damaged or lost to wildfire. Data Certainty: High

Drought conditions may mean the very small number of managed meadows remaining in the PDNP would be more susceptible to grassfires. The resulting bare ground could more easily be eroded. However, this risk is considered minimal, and unlikely to have a meaningful impact on the long-term structure or extent of patterns of enclosure. Data Certainty: Low

# Nutrient changes or environmental contamination

Wetter winters may increase the perceived need for fertilizer application if leaching increases. In addition, pressure from ‘pest’ species due to warmer winters may lead to an increase in pesticide application. Both factors could affect hedgerow plants – decreasing the diversity and condition of the species they contain. Drift from pesticide application would also lead to the loss of lichens and bryophytes on stone walls. This would negatively affect invertebrates and other wildlife living in hedgerows and stone walls, and change the character of the components which make up the patterns of enclosure. Data Certainty: Low

# Sedimentation or erosion

Dry stone walls and boundary markers are sensitive to stability of soils under the base. They may be damaged if wetter winters saturate the ground, and extreme storm events become more frequent resulting in high levels of surface run-off. Hedges are also sensitive to this change. This could lead to the acceleration of damage and a decrease in structural stability due to run off. Structures on clay soils are likely to be most vulnerable. Increased maintenance costs could see some areas of dry stone walling replaced with fencing which may alter the landscape character. Data Certainty: High

# What is the adaptive capacity of boundaries and patterns of enclosure?

Overall adaptive capacity rating |  |

There are very diverse patterns of enclosure across the PDNP when taken as a whole, meaning that there is a high chance of some types surviving in their current form despite future impacts. Hedgerows are composed of different woody species. Hedges with low diversity, for example holly only, have lower adaptive capacity than mixed-species hedges and are therefore more vulnerable. Many PDNP hedgerows are in poor condition with lots of gaps and low diversity with only one or two species. Data Certainty: High

However, they have a good chance of recovery from change, especially with planting to fill in any large gaps. Areas where dry stone walls and hedges are less continuous and have not been well maintained are likely to be less resilient to change. Data Certainty: Moderate

Dry-stone walls vary in building material and method of construction. Single walling is likely to be less resistant to damage than thicker double walls. Dry stone walls require continuous maintenance in order to recover from change, completely depending on the level of human management. Data Certainty: Moderate

Limestone walls may be at a higher risk of erosion and weathering than gritstone walls, but this will vary by location. Data Certainty: Low

In terms of fossilised strip field boundaries, those found on the fringes of the area that are demarked by hedges may be less resilient than those marked by walls which tend to be found on the plateau itself. Data Certainty: Low

Environmental land management schemes are available for the restoration and management of both hedgerows and stone walls. There are other funds available to restore walls through PDNPA and Natural England but these are variable and now much reduced. Some funding options are likely to be available in the future for maintaining landscape - however options are likely to remain limited and current trend is that land in the PDNP with an agreement is declining. It is not known what future priorities will be. Any funding available will be vital for offsetting the effects of climate change. Data Certainty: High

In the majority of cases, planning permission is needed to make changes to agricultural land or commercial property. The system of control over land use change within the park should offer at least a partially effective mechanism for conserving the landscape. However, changes will still occur if keeping livestock on pasture becomes economically unviable or there is pressure to intensify land use. Data Certainty: Moderate

Important hedgerows are protected by the Hedgerows Regulations 1997. Stone walls are not legally protected however government guidance states that only in special cases can a stone wall be removed or stone take from it. Some protection is also provided through the Environmental Impact Assessment regulations. Future environmental land management schemes or cross compliance may include protection of dry stone walls, especially if they are of a certain length of historic or landscape importance, however this is currently unclear. Stricter policies or regulations could help enforce maintenance of existing walls. Data Certainty: High

Hedgerows have a good chance of recovery from change, especially where planting occurs to fill in any large gaps. Although species composition of some hedges may change due to of climate change, their overall function should remain. Dry-stone walls need management and maintenance to survive and recover from change. They therefore have good potential for resilience provided human intervention occurs. Data Certainty: Moderate

A good level of information and skill is available to make appropriate adaptations and to deal with most climate changes, especially for hedgerows. Dry stone walling is slowly becoming popular again, however there is still a skills shortage. There is extensive knowledge about different construction methods and how to best repair or reconstruct a wall. Advice is available from The Dry Stone Walling Association. Prehistoric field systems have a much lower adaptive capacity as they generally survive as earthworks. Because of diversity in land ownership, a great diversity in management, information and skills available to adapt and conserve the landscape it is likely that some features will survive whilst some will decline. The PDNPA’s Historic Landscape Character Assessment is vital to understand how existing patterns relate to past land use and may provide important understanding of how we manage land in the future. Data Certainty: Moderate

# Key adaptation recommendations for boundaries and patterns of enclosure:

# Improve current condition to increase resilience

The current condition of a feature is an important factor alongside its sensitivity and exposure, in determining its vulnerability to climate change. These recommendations are aimed at improving the condition of the feature at present, therefore making it better able to withstand future changes to climate.

- Monitor boundary changes at a landscape scale, for example quantify the loss of walls and hedges. Ensure that management mitigates piecemeal changes to enclosure patterns that may seem insignificant on their own, but that can have cumulative and large impact upon landscape character over time.

- Encourage the use of agricultural buffer strips to protect hedges from human behaviour changes (e.g. intensification of agriculture) which may occur because of climate change.

- Ensure management practices allow for the maintenance of walls and historic field patterns. Explore opportunities in future environmental land management schemes.

- Undertake research to understand the significance of different boundary types and patterns. Appreciate that boundaries may have different components, including natural features. Also appreciate the time-depth in enclosure. For example, prehistoric boundary patterns may underlie the dominant, later enclosure patterns, and be visible only as earthworks. This will help inform future adaptation planning.

- Help land managers within the PDNP to enter into environmental stewardship type agreements or secure funding for capital works by providing assistance with advice and logistics - see Moors for the Future Partnership’s Private Land Project as a possible model.

- Consider the impact on key views when planning adaptations.

# Improve current condition to increase resilience: Targeted conservation efforts for important sites and at risk areas

The current condition of a feature is an important factor alongside its sensitivity and exposure, in determining its vulnerability to climate change. These recommendations are conservation measures aimed at those sites that will have the biggest impact for this feature – either because they are particularly important for the feature or because they are most at risk from climate change.

- Focus efforts on identifying priority areas and restoring and reconnecting fragmented hedges and walls in those areas. It is important to avoid further loss and restore boundaries. This will improve their function as wildlife corridors and improve their overall resilience to change. Ensure targeted conservation efforts are informed by historic character and relative significance.

# Improve current condition to increase resilience: Increase structural diversity to improve resilience at a landscape scale

The current condition of a feature is an important factor alongside its sensitivity and exposure, in determining its vulnerability to climate change. These recommendations focus on increasing the structural diversity of the area or habitat in which the feature is found. This can help to offset the effects of climate change on the feature, as well as to allow it to be in a better position to recover from future climate changes.

- Diversify the landscape and increase the proportion of tree cover to reduce the impact of flooding from rivers and overland flow on boundaries.

- Restore and connect fragmented hedges with native species sourced from further south in the UK. Increase species diversity of hedges to buffer against single species losses.