Feature Assessment: Built Environment / Country houses

# Country houses

| Overall vulnerability |  |

# Features assessed:

- Iconic country houses in parkland settings

- Stately homes and parkland

- Grand halls of the landed gentry

# Special qualities:

- Characteristic settlements with strong communities and traditions

- An inspiring space for escape, adventure, discovery and quiet reflection

# Feature description:

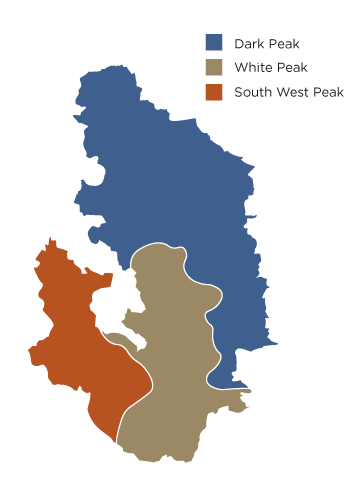

Country houses are often surrounded by parkland and designed landscapes. Some houses can be described as stately homes, which are impressive structures and sometimes include houses that are open to visitors. Grand halls of the landed gentry are another sub-category of country house. They were lived in historically by the landed gentry, a landowner social class.

The PDNP contains many iconic country houses in parkland settings, for example Chatsworth House, Haddon Hall, Thornbridge Hall, Lyme Park, Hassop Hall, Ashford Hall, Stanton Hall, Swythamley Hall and Tissington Hall. These properties are privately managed and owned, apart from Lyme Park which is primarily managed by National Trust and supported by the Stockport Corporation.

Country house infrastructures are historically significant and homes often hold many historical archives and artefacts, for example paintings, sculptures and pottery, and archives. Parkland landscapes have been designed over time; they hold great ecological importance as they have diverse and unique habitats supporting various species and great archaeological importance that reflects the landscape they were developed from as well as their own development over time. These grounds are often used for leisure and recreational purposes such as walks and sporting events, making them also culturally important. They hold significance for a wide range of people and are frequently used for educational visits by both adults and children.

# How vulnerable are country houses?

Country houses and associated features in the PDNP have been rated ‘moderate’ on our vulnerability scale. This score is due to high sensitivity and exposure to climate change variables, but a generally well managed current condition and a high adaptive capacity.

An increase in extreme climates, pests and diseases may pose a threat to species which define the character of the gardens at these homes and the historical archives contained within them. Changes to landscape may affect people’s desire to visit, decreasing the amount of resources available to protect the building and grounds from further harmful effects brought on by changes to climate. If they are well managed and resourced, country houses and their parkland settings have a high adaptive capacity.

# Current condition

Country houses are currently mainly well managed, however this is dependent on the resources available. They are affected by non-climate stressors, such as damage caused by visitors, but this has limited impact on their quality or function as it is often mitigated through maintenance. There are invasive species present which do impact the associated parkland, for example Rhododendron at Chatsworth House. Parkland at Lyme Park has already been damaged due to wildfire and parkland at some sites has already been lost entirely to development and agriculture.

In the summer of 2019 Lyme Park suffered from flooding. This saw some of the outbuildings damaged as well as the park and garden.

The majority of the country houses in the PDNP are listed and none are on Historic England’s Heritage at Risk Register.

# What are the potential impacts of climate change?

| Overall potential impact rating |  |

# Direct impacts of climate change

Multiple climatic changes may lead to increased flooding, rainfall, frost and drought, which could all directly impact country houses and parklands.

Within country houses, items such as wallpaper, decorative surfaces and paintings rely on a stable climate for their maintenance and conservation. Electronic equipment which ensures the functionality of these buildings also relies on a stable climate to work correctly. Therefore items within country houses could be vulnerable to damage if extremes of temperature and rainfall become more frequent. All these items can also be easily lost entirely to frost fracture or flooding from extreme temperatures or precipitation. Data Certainty: High

Old buildings which do not have adequate modern rainwater goods such as guttering and downpipes may not be able to cope with increases in rainfall, making them sensitive to damage. Data Certainty: High Wooden buildings could be particularly susceptible to rot and historic leadwork could risk erosion from wetter conditions. Data Certainty: High Drought may damage the structural stability of buildings. Data Certainty: Moderate

Increased rainfall leading to standing water conditions could also result in damage to parkland and gardens. An increase in storm events could damage old parkland trees. Conversely, reduced rainfall in summer could also negatively impact these landscaped gardens. If plant species are reliant on rainfall, the species composition of designed landscapes may be altered. Data Certainty: High

Other structures, for example statues or fountains, can have footings made from certain geologies such as clay. These could dry under drought conditions and eventually collapse. Other historical structures may be sensitive to geological shrinking and swelling, for example grottos made from mortar. Data Certainty: High

# Invasive or other species interactions

Atmospheric pollution coupled with an increase in temperatures could mean that new flora, fauna and invasive or nuisance species spread into parklands, or that existing species spread further and become a nuisance. Higher levels of precipitation, flooding, storm events or humidity can also worsen the impact of this by encouraging the spread of diseases or pests. Data Certainty: High

Some species in parklands, particularly trees, are sensitive to pathogens and therefore may be lost. One example of this is box blight fungus, which browns box leaves and causes branch dieback. Another is ash die back (see Slopes and Valleys with woodland). New species that are spreading into parklands also have the potential to bring unknown pests and diseases for example insect and fungal infestations. These insect and fungal infestations could then harm buildings and organic artefacts, meaning important historical objects could be damaged or lost. Infrastructure built with traditional materials may be more difficult to repair if materials are less easy to source. This could result in modification to the appearance of the designed landscapes and buildings, making them less desirable places to visit. Data Certainty: High

Higher levels of precipitation and humidity could also increases incidences of mould and pests, such as common furniture beetles, weevils or silverfish. Within country houses, collections with cultural importance and interior furnishings could become vulnerable to damage or loss from mould or pests. Data Certainty: High

An increase in flooding and storm events may mean that gardens and structures are left under water for prolonged periods of time. This could make them vulnerable to an increase in pests and diseases, leading to damage or loss of species or structures, potentially altering the landscape. Data Certainty: Moderate

Increased carbon dioxide and nitrogen levels from atmospheric pollution could result in an accelerated growth rate of invasive or nuisance species. Country houses and garden ornaments, for example fountains or statues, may be vulnerable to structural damage caused by this increased plant growth. These can include ivy, Japanese knotweed, algae, moss, and an overgrowth of trees and scrub. Parkland may be susceptible to bracken or Rhododendron overgrowth, which could result in more grounds maintenance being required and therefore higher running costs. Data Certainty: Moderate

# Human behaviour change

Human behaviour changes as result of climate change have the potential to bring about various landscape and building structure alterations to country houses and parklands.

Hotter, drier summers may cause competition for water availability, changing how much is available to irrigate parks and gardens. It is possible that drought tolerant species will be more suited to the new environment and will outcompete drought sensitive species. This could change the aesthetics of the lawns and gardens within the parkland. Data Certainty: Moderate

Hotter, drier summers may also lead to an increase in visitor numbers which may damage parklands due to more foot traffic. More car parking spaces are likely to be needed to accommodate this increase in recreational use, expanding into parkland fields and damaging them. Data Certainty: Low

Severe or frequent flooding of parkland may make it unsuitable for grazing animals. In their absence this could allow scrub to develop where it was previously kept under control, changing the character of the parkland. Conversely, flooding of land elsewhere could increase stocking levels and result in over grazing by sheep or deer in parklands. Data Certainty: Low

A combination of climate change stressors may mean that the installation of insulation is required to improve thermal efficiency. This has the potential to decrease ventilation and increase the rotting of wood that makes up the frame of buildings and supports their slate roofs, leading to structural damage of the houses. Data Certainty: Low

# Sedimentation or erosion

Erosion could result from more frequent and severe flooding and it could damage houses and parklands. Parkland and its associated buried floodplain archaeology and structures, for example bridges, may be damaged by erosion from high energy floods. Data Certainty: High Fallen trees will further increase the risk of erosion and add to the damage of bridges and structures that are within the flood path. Data Certainty: Moderate

# Other indirect climate change impacts

Hotter, drier summers could result in more frequent or severe wildfires. Parklands could be susceptible to wildfire damage, especially those with surroundings that are more prone to wildfire such as woodland or moorland. Building structures and materials could also suffer due to wildfire damage, as wooden buildings would be particularly susceptible. Data Certainty: High

# What is the adaptive capacity of country homes?

Overall adaptive capacity rating |  |

The preservation of these country houses is largely dependent on the availability of economic and technological resources. A large pool of finances and expertise are available to Chatsworth House and Lyme Park; Chatsworth House is part of the long-established Devonshire Estate and Lyme Park is managed by the National Trust. Privately managed properties, for example Haddon Hall or Thornbridge Hall, are generally assumed to have sufficient financial resources, however this cannot be fully relied on. Advice on climate change adaptations is available from Historic England. Grants for adaptation may also be available however privately owned or managed properties often have less access to grants than charities. This can make them less financially resilient and therefore less likely to install adaptation measures. Data Certainty: High

Parklands often include a large variety of plant species and can include multiple different landscape types. This diversity makes them more resilient to future climate impacts. It is possible that they already include species or habitats that are more suited to future climate changes and will therefore continue to exist. Less diverse landscapes will be more vulnerable than their counterparts, so gardens can be designed with climate change stressors in mind to ensure they include a variety of suitable plant species. Trees are a defining aspect of parkland but there is less scope for selecting trees to plant that can cope with future climate stressors, therefore putting that aspect at greater risk. Data Certainty: Moderate

Country houses are often listed buildings which can provide some protection against inappropriate management techniques being used. Their condition is monitored so any problems arising can be addressed and the Heritage at Risk Register tracks some of the most vulnerable listed buildings and structures. It is more likely that action will be taken on listed buildings over non-listed buildings, and there is skill and information available to make adaptations and deal with damage to listed buildings from Historic England and PDNPA. Data Certainty: High

Some parks are registered but this does not give them much additional protection unlike that provided for scheduled monuments and listed buildings. There is more formal protection for historic parklands within a Site of Special Scientific Interest, and there are Environmental Stewardship options available which provide funding to protect biodiversity and conserve natural resources. Additionally, the Gardens Trust is consulted about any planning permission applications on landscapes listed on Historic England’s Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest. Historic England also need to be consulted on planning applications in areas with Grade I & II* listed structures and buildings. This can help protect these country houses and parklands. Data Certainty: High

Restoration of country houses following damage from weather events is possible but likely to come at huge cost. Damaged gardens can be replanted but old mature trees and local plant species such as orchids are difficult to replace. Although any new climate change adaptations will reduce the risk of damage and loss, they may be difficult or costly to install or alter the aesthetics of a property. The National Trust has done work already elsewhere in the UK to increase the water capacity of downpipes so they can better handle large volumes of water in storm events. Data Certainty: High

c## What is the adaptive capacity of country homes?

Overall adaptive capacity rating |  |

The preservation of these country houses is largely dependent on the availability of economic and technological resources. A large pool of finances and expertise are available to Chatsworth House and Lyme Park; Chatsworth House is part of the long-established Devonshire Estate and Lyme Park is managed by the National Trust. Privately managed properties, for example Haddon Hall or Thornbridge Hall, are generally assumed to have sufficient financial resources, however this cannot be fully relied on. Advice on climate change adaptations is available from Historic England. Grants for adaptation may also be available however privately owned or managed properties often have less access to grants than charities. This can make them less financially resilient and therefore less likely to install adaptation measures. Data Certainty: High

Parklands often include a large variety of plant species and can include multiple different landscape types. This diversity makes them more resilient to future climate impacts. It is possible that they already include species or habitats that are more suited to future climate changes and will therefore continue to exist. Less diverse landscapes will be more vulnerable than their counterparts, so gardens can be designed with climate change stressors in mind to ensure they include a variety of suitable plant species. Trees are a defining aspect of parkland but there is less scope for selecting trees to plant that can cope with future climate stressors, therefore putting that aspect at greater risk. Data Certainty: Moderate

Country houses are often listed buildings which can provide some protection against inappropriate management techniques being used. Their condition is monitored so any problems arising can be addressed and the Heritage at Risk Register tracks some of the most vulnerable listed buildings and structures. It is more likely that action will be taken on listed buildings over non-listed buildings, and there is skill and information available to make adaptations and deal with damage to listed buildings from Historic England and PDNPA. Data Certainty: High

Some parks are registered but this does not give them much additional protection unlike that provided for scheduled monuments and listed buildings. There is more formal protection for historic parklands within a Site of Special Scientific Interest, and there are Environmental Stewardship options available which provide funding to protect biodiversity and conserve natural resources. Additionally, the Gardens Trust is consulted about any planning permission applications on landscapes listed on Historic England’s Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest. Historic England also need to be consulted on planning applications in areas with Grade I & II* listed structures and buildings. This can help protect these country houses and parklands. Data Certainty: High

Restoration of country houses following damage from weather events is possible but likely to come at huge cost. Damaged gardens can be replanted but old mature trees and local plant species such as orchids are difficult to replace. Although any new climate change adaptations will reduce the risk of damage and loss, they may be difficult or costly to install or alter the aesthetics of a property. The National Trust has done work already elsewhere in the UK to increase the water capacity of downpipes so they can better handle large volumes of water in storm events. Data Certainty: High

# Key adaptation recommendations for country houses

# Improve current condition to increase resilience

The current condition of a feature is an important factor alongside its sensitivity and exposure, in determining its vulnerability to climate change. These recommendations are aimed at improving the condition of the feature at present, therefore making it better able to withstand future changes to climate.

- Have emergency plans in place for limiting damage during major climate events.

- Include country houses and their parklands in landscape scale flood risk management plans.

- Increase the resilience of the surrounding landscape to help create a buffer for these country houses and parklands. Form estate level plans for improved climate resilience, such as improving moorland condition to reduce flood risk.

- Consider collections and archives that could be at risk, and store those that are potentially vulnerable to damage from water, pests and overheating in places where these impacts will be smaller.

- Remedial work completed after damage has occurred should be appropriate for the specific building. See Historic England’s 2010 (2015 edition) document ‘Flooding and Historic Buildings’ for examples.

- Undertake appropriate ecological and archaeological surveys to ensure that any plans are as fully informed as possible.

# Adapt infrastructure for future conditions

These recommendations are adaptations to physical infrastructure that should allow the features to better resist or recover from future climate change.

- Install rain harvesting and storage facilities at sites which are sensitive to drought. This is already in place at some properties.

- Keep abreast of new research into the performance of alternative materials for future climate adaptations.