Feature Assessment: Habitats / Meadows

# Meadows

| Overall vulnerability |  |

# Feature(s) assessed:

- Meadows and flower-rich grasslands

- Wildflower meadows

- Hay meadows

- Unimproved pastures and meadows (and road verges)

# Special qualities:

- Beautiful views created by contrasting landscapes and dramatic geology

- Internationally important and locally distinctive wildlife and habitats

- Landscapes that tell a story of thousands of years of people, farming and industry

# Feature description:

The ‘meadows’ category is comprised of unimproved lowland (mostly neutral and enclosed) grasslands across the PDNP. It focusses on wildflower rich areas and those cropped for hay in particular, but also applies to flower rich pasture and non-agricultural settings which may be rich in wildflowers such as roadside verges or church yards.

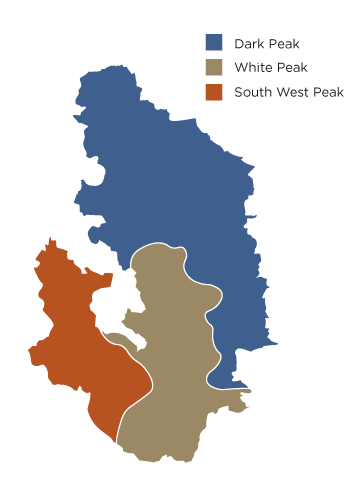

Approximately 1,700 hectares of lowland meadows are mapped – representing only 1.2% of the area of the PDNP. These meadows are all considered priority habitat in the PDNP. Approximately 70% of what remains can be found in the White Peak, 20% in the South West Peak and 10% in the Dark Peak. Of the total area recorded, around 50% has been categorised as hay meadow.

The PDNP hay meadow survey found there to be six community types in the PDNP, but there is potential for more discoveries to be made as only some meadows in the South West and Dark Peak were surveyed. Of the known communities, some, such as flood plain meadows, represent only a few fields making them rare in the PDNP.

Meadows are an important feature for biodiversity. A meadow in good condition can contain more than 50 plant species as well as provide habitat for mammals, invertebrates, and rare and declining bird species such as skylark and twite. Meadows are rich in grass and grass-like species as well as flowering broad-leaved herbs, and provide a vital refuge for biodiversity in an agricultural landscape, breaking up areas of silage fields and adding diversity to the landscape mosaic. Hay meadows are also a traditional feature of the landscape with ancient cultural significance, and may even predate churches in some villages.

# How vulnerable are meadows?

Meadows and associated features in the PDNP have been rated ‘high’ on our vulnerability scale. This score is due to high sensitivity and exposure to climate change variables, coupled with a varied current condition and highly fragmented habitats, but with a moderate adaptive capacity.

Meadows are already in a poor state in the PDNP, with only a few small patches with very limited connectivity remaining. Climate change impacts are unavoidable; key plants and their associated species may be lost. Some meadow species will be unable to thrive with changes in weather, leading to habitat change. Agricultural intensification caused by pressure to grow more food may lead to further habitat loss. A mismatch between flowering and pollination timings may lead to a decrease in some plants. Pollution may cause changes to soil composition. Hay-making may become difficult due to unpredictable weather. Overall, climate change stressors are likely to lead a loss of habitat and biodiversity.

# Current condition:

Meadows are in very poor condition nationally, with a 97% decline in flower-rich grasslands between the 1930s and mid-1980s almost wholly due to changes in agricultural practices. This loss has continued in the PDNP, the Hay Meadows Project recorded a 50% loss between the mid-1980s and mid-1990s with a further 26% declining in interest, and then a further 25% loss or quality decline between 1995 and 1998. The rate of loss has varied greatly, but intensification of dairy farming has been identified as a leading factor in areas such as Peak Forest. Only a very small portion of the meadows present 80 years ago remain.

The habitat has become highly fragmented and localised across the whole of the UK including in the PDNP. There are few surviving flower-rich hay meadows which support species such the as oxeye daisy and yellow rattle. Some areas of meadow are protected as Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs) in the PDNP, but many meadows are not covered. Condition is variable even within SSSI sites, and data is limited for those areas not covered by SSSI designation or owned by a Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) such as National Trust or a County Wildlife Trust, though many are covered by environmental land management agreements. Meadows in the limestone dales are generally in better condition and have higher connectivity, but these areas are still relatively small.

As meadows are a habitat created and maintained by human intervention, changes in management have a great effect on their condition. There has been a change towards silage making rather than haymaking, a technique that promotes vigorous grass growth through multiple cuttings, often supported by fertiliser and broadleaved herbicide. Much of the floristic diversity of unimproved meadows is then lost in as annuals are prevented from setting seed and broadleaved herbs are eliminated. This is a direct cause of the catastrophic loss of meadowland over the past 80 years, and continues to be a risk for unprotected sites. Meadows have also been lost to pasture land, in which livestock are not removed during the main growing season or where there is increased use of fertilisers and herbicides, leading to a reduced sward height and loss of broad-leaved herbs and lower plant diversity.

Fast growing ruderal species such as hogweed, spear and creeping thistle, cow parsley, and nettle can dominate areas of meadow. Though these are native species and have a place in the grassland assemblage, their tendency to dominate has led to their status as weeds. These species are particularly prevalent on fertilised sites, as excess nutrient input allows them to outcompete other broadleaved plants. Roadside verges which could harbour meadow species are also prone to invasion of this kind due to their disturbed nature and poor management, combined with the addition of nitrogen which is greater along roads with more traffic.

# What are the potential impacts of climate change?

| Overall potential impact rating |

# Direct impacts of climate change

Changes in annual precipitation cycles could have consequences for meadow plant communities. Waterlogging in winter and dry ground in summer would give a competitive advantage to stress tolerant and ruderal plants. Characteristic meadow species that are particularly drought sensitive such as red clover could be lost from some meadows. This happened in some areas during the hot and dry summer of 2018, particularly on south facing slopes in the first instance. Higher spring soil moisture levels may also increase total biomass and favour more competitive species such as grasses, at sites where phosphorus in not a limiting factor. These effects could combine to change the composition of some meadows, with some species dominating at the expense of the usual assemblage. Data Certainty: High These effects could be compounded by an increase in winter storms and summer droughts, causing ground conditions to more often be at extremes of moisture. Increased flooding could be particularly damaging to floodplain meadow communities, which are vulnerable to larger and longer flood events. This could cause floodplain meadow communities to transition to low diversity swamp or inundation grassland communities. As there are only a few sites in the PDNP, this could cause them to be lost entirely. Data Certainty: Low

Earlier warm conditions may change the phenology (timing of natural events) of some meadow plants, causing them to flower and set seed earlier. This may lead to phenological mismatches such as reduced pollen and nectar availability for invertebrates and reduced seed availability for bird species. Higher temperatures and a longer growing season may also give a competitive advantage to fast growing species, reducing the diversity of meadows in some areas. Higher temperatures will move the climate envelope northwards, meaning some species at the southern edge of their range may decline, while southern species that are capable of long-distance dispersal expand their range northwards. Warmer winters will also reduce vernalisation, a process by which the prolonged cold of winter is a cue for winter dormancy and spring flowering in some plants. Species that require vernalisation such as yellow rattle and cowslips may therefore be disadvantaged and outcompeted by species that do not. Data Certainty: High

Increased winter rainfall may lead to higher deposition rates of nitrogen, and other atmospheric pollutants could cause increased acidification. Acidification can have a variety of effects, including increased concentrations of toxic ammonium, increased solubility of aluminium and other toxic cations, and reduced phosphorous availability. These effects combined would disadvantage sensitive plants, reducing the floristic diversity and value of meadows. However this may be offset be landowners adding more lime to maintain existing plant cover. Data Certainty: Moderate

# Human behaviour change

Haymaking practices could be affected in numerous ways, but the increased variability of weather makes this hard to predict. Traditional haymaking relies on warm, dry, settled weather to facilitate the drying of hay after cutting, and it is here that there is uncertainty as to the effects of climate change. Climate change will mean warmer, drier summers, which could make haymaking more viable as drying hay becomes easier. Haylage, in which hay is not left to dry for as long, would also be affected to a lesser extent, potentially making it more desirable than silage making. Data Certainty: Moderate However, extreme weather events such as storms are also predicted to become more frequent, meaning that unpredictable heavy rainfall may prevent or delay haymaking, reducing its already limited economic viability. Data Certainty: Moderate Increased productivity due to increased temperatures could also cause a reduction in hay meadow diversity over time due to change in management. More productive meadows may be cut earlier, before seed is set, preventing annual regeneration. Data Certainty: Moderate Drier summers may also mean that some sites are abandoned due to the crop dying off prematurely. Cessation of management would mean that some meadows are lost as they succeed to other grassland or woodland habitats, or a different management regime is taken up. However, reduced management of fields in other areas may allow some natural meadow generation. Data Certainty: High

Wetter, warmer springs causing increased vegetative growth in areas that are not nutrient limited could make frequent cutting desirable for landowners. Frequent cutting encourages grasses to dominate, reducing the species diversity and changing the community composition. This effect is especially pronounced when cuttings are left to lie, creating thick ground cover and increasing the nutrient input from the dead plant matter. This practice is common on verges, where sward heights may regrow more quickly and ruderals such as rosebay willowherb move in to disturbed areas and dominate, boosted by the additional nitrogen input from traffic. Data Certainty: High

Warmer weather earlier in the year may mean that cutting dates are also earlier. This would have a negative impact on ground-nesting birds on undesignated sites, as some may still be breeding or nesting, and would be negatively affected by machinery and disturbance. As silage cutting makes much farmland uninhabitable, disturbance at those sites remaining could be quite damaging. Data Certainty: High

Changes in water usage could have a large impact on floodplain meadows, particularly in lower areas of the PDNP. While there are controls in place, increases in water abstraction during dry spells could dry out some sites and change their community composition to more similar non-floodplain meadow types. Data Certainty: Moderate

# Invasive or other species interactions

Changes in water levels are likely to increase the sensitivity of meadows to dominance by generalist and ruderal species by increasing disturbance. Summer droughts leaving bare ground could magnify this effect, opening up space for ruderals to colonise. Community composition would be altered as less competitive species, including many characteristic meadow species, are replaced by generalist meadow species or opportunist ruderals and invasives. Data Certainty: Moderate Riverside and floodplain meadows are also at increased risk of colonisation by invasive species such as Himalayan balsam as winter flooding could spread seeds over large areas. Data Certainty: High

# Nutrient changes or environmental contamination

Increased flooding in riverside meadows could cause an increase in nutrient deposition. Nitrogen and phosphorous enter the watercourse via pollution in runoff, and can be deposited onto meadows during flood events. Increased nutrient availability could provide an advantage to faster growing plants such as grasses, pushing out some meadow species and changing community composition. Data Certainty: Moderate Sedimentation or erosion

Higher flows during winter could cause greater erosion in meadows, particularly those near waterways. This effect could be compounded by the presence of Himalayan balsam on riverbanks, which dies back in winter leaving the ground bare and the banks more vulnerable to erosion. This would lead to losses on the edges of meadows and a reduction in habitat. Wetter soils are also more sensitive to trampling, increasing erosion in waterlogged conditions, which will be more prevalent in wetter winters. Data Certainty: Moderate

# What is the adaptive capacity of meadows?

Overall adaptive capacity rating |  |

Meadows in good condition are very diverse in plant species, with the best holding well over 50 different plant species. This diversity means that the small number of meadows currently in good condition will have the highest ability to resist or adapt to the effects of climate change. It must be accepted that some northerly-distributed species, such as great burnet and lady’s mantle, will decline or be lost from some sites. Data Certainty: Moderate However, meadow assemblages can vary, with the broad requirements of a meadow simply being a high diversity of grass-like and broadleaved herbs. Therefore, while some species may be lost from meadows and the community composition changed, meadows themselves are unlikely to be lost. Some species that are lost, for example those at the southern edge of their range, may be replaced by other species that fill their niche, such as other generalist species in the sward or southern species with northern range expansions. Data Certainty: High Meadows in the PDNP are generally highly fragmented with low connectivity, so this replacement of species and gradual shift in diversity would be slow. Data Certainty: High

Meadows have some level of protection though designation and ownership. Some are owned by the National Trust, PDNPA, County Wildlife Trusts or a few are designated as SSSIs, and many in private ownership have an environmental land management scheme aimed at maintenance or restoration. Data Certainty: High Although PDNPA can make recommendations on meadow management, it has no statutory capacity to enforce management on privately owned land, although private land is still covered by Environmental Impact Assessment regulations and has some level of protection. Data Certainty: Moderate As a managed environment, meadows have the advantage of management adaptation to withstand some climate change effects. However, this may be difficult to practically implement due to the currently low economic incentives to create and maintain meadows.

# Key adaptation recommendations for meadows:

# Improve current condition to increase resilience

The current condition of a feature is an important factor alongside its sensitivity and exposure, in determining its vulnerability to climate change. These recommendations are aimed at improving the condition of the feature at present, therefore making it better able to withstand future changes to climate.

- Many more restored meadows are needed in the PDNP if effective nature recovery networks are to be developed. These would increase carbon storage and capture, increase resilience to climate change and drought especially, provide transitional sites between existing habitats, plus better habitat for invertebrates and other animals. Species rich meadows are much better for a healthy stock animal as well – though less productive than heavily fertilised pastures, they provide a more diverse, healthy diet, better ways of managing health – many old ones were called hospital fields, and are essential for a low input low output system.

- Opportunities to extend and enhance the management of existing unimproved grasslands should be sought, for example in “Riverside Meadows” where grasslands could enhance their role for flood water storage, helping to reduce flood impacts further downstream.

- Encourage the creation and enhancement of wildflower meadow in non- agricultural settings e.g. recreational areas, churchyards, verges and residential gardens. A scheme to help with conversion or management may be required.

- Non-climate sources of harm (for example conversion to silage or permanent pasture; application of high fertilizer levels, early cutting) should be minimised to ensure maximum possible resilience.

- Identify and preserve refugia for species at their southern range limit - look at aspect and topography and ensure sites are sensitively managed.

- Consider the impact on key views when planning adaptations.

# Improve current condition to increase resilience: Increase structural diversity to improve resilience at a landscape scale

The current condition of a feature is an important factor alongside its sensitivity and exposure, in determining its vulnerability to climate change. These recommendations focus on increasing the structural diversity of the area or habitat in which the feature is found. This can help to offset the effects of climate change on the feature, as well as to allow it to be in a better position to recover from future climate changes.

- Species rich meadow should be one of the key habitats to be considered when other habitat types are no longer viable due to climate change. Rush-pastures which have become too dry could be converted.

# Adapt land use for future conditions

These recommendations are adaptations to the way in which people use the land. Flexibility in land management - reacting to or pre-empting changes caused by the future climate - should afford this feature a better chance of persisting.

- Greater flexibility in site management will be needed - e.g. Timing of hay cut and grazing.