Feature Assessment: Habitats / Woodland

# Woodland

| Overall vulnerability |  |

# Feature(s) assessed:

- Woodlands and scrub

- Veteran trees, wood pasture, hedgerows

# Special qualities:

- Beautiful views created by contrasting landscapes and dramatic geology

- Internationally important and locally distinctive wildlife and habitats

- Undeveloped places of tranquillity and dark night skies within reach of millions

- An inspiring space for escape, adventure, discovery and quiet reflection

- Vital benefits for millions of people that flow beyond the landscape boundary

# Feature description:

Woodlands occur on a range of soils, producing different types defined by their dominating species and growth patterns. The five main types of woodland found in PDNP are 1) upland mixed ash woods, 2) upland oak/birch woods, 3) veteran trees, wood pasture and parkland, 4) plantations which are conifer, broadleaved, and mixed, 5) scrub and hedges. Areas of ancient woodlands often have a more mixed species composition where they are found in the PDNP, and so may not fit exactly into these categories. Smaller patches of woodland, such as shelterbelts, in-field and boundary trees, are also found throughout the PNDP. Wet woodland is present but this is discussed separately.

The PDNP is poorly wooded compared to the UK and European averages with varying levels of fragmentation. Approximately 5,000 hectares of woodland has been mapped in the PDNP, 3,500 ha of this being priority habitat. An additional 10,500 ha of scrub has also been mapped, largely as non-priority habitat. 60 ha of mapped woodland is ancient woodland or plantation on ancient woodland sites. Ancient woodlands are a refuge for biodiversity, containing many species that require long established woodland. As a result, ancient woodlands are a valuable resource that are not easily replaced. Plantations on ancient woodlands, often coniferous rather than native broadleaf, still harbour many of these ancient woodland indicator species and have the potential for high biodiversity if restored.

Some woodland habitats are nationally and internationally important for their flora and fauna. Ash woods in the dales and oak woods in the Dark Peak and South West Peak are both Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) features. Upland mixed ash woods are listed as a priority habitat under Annex 1 of the European Union Habitats Directive (as Tilio-Acerion ravine forests). They are rich habitats for wildlife with many nationally important species such as small and large-leaved lime, lily-of-the-valley, white-spotted pinion moth, and lemon slug. At the south-eastern edge of their range in Britain, upland oak/birch woods, also an EU Habitats Directive priority habitat, support a range of irreplaceable ancient woodland species. The ground flora here includes yellow archangel, dog’s mercury and wood anemone, along with upland birds like pied flycatcher and wood warbler, and invertebrates such as northern wood ant, ash-grey slug and the purple hairstreak butterfly.

Less extensive and non-native woodland types are also important for biodiversity, often as part of a wider landscape mosaic. Plantations can provide habitat for bird species such as crossbill and nightjar in felled areas. Veteran trees are important for rare invertebrates, lichens, fungi, bats and breeding birds. Parklands with veteran trees are also of national importance; For example, Chatsworth Old Park is a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI).

Scrub and hedges are valuable feeding habitat for birds, particularly in winter when they provide berries for species such as fieldfares and redwings. All woodland types host a variety of fungi, ferns, mosses, liverworts, and lichens. The historic nature of ancient woodland sites means they can also hold important archaeological records such as charcoal pits.

# How vulnerable are woodlands?

Woodlands in the PDNP have been rated ‘high’ on our vulnerability scale. This score is due to high sensitivity and exposure to climate change variables, coupled with a poor fragmented current condition, and a moderate adaptive capacity.

Woodland condition in the PDNP is variable, with smaller patches generally in poor condition, but larger areas under SSSI protection faring better. Smaller woodlands with low tree species diversity are likely to be more vulnerable than those that are larger and more diverse. The area of woodland in the PDNP may be reduced by climate change, especially single species woodlands, though the demand for climate change mitigation may encourage new woodland creation.

# Current condition:

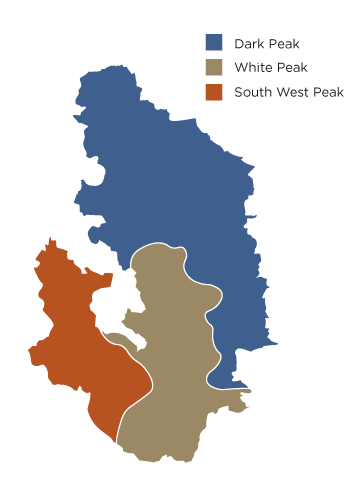

Woodlands in the PDNP have varying levels of protection. Many woodlands in the White Peak are designated within SSSIs. Other woodlands, outside designated sites, in the Dark Peak, White Peak and South West Peak are managed or part-managed by National Trust, Natural England, estates, and local Wildlife Trusts. Veteran trees, wood pasture and larger patches of ancient woodlands are generally protected through designation or management plans. Individual trees can also be protected through Tree Protection Orders. However those trees and woodlands outside SSSI sites and conservation ownership are left with no protection.

Larger native mixed ash woodlands in the White Peak are mostly in good condition although they are threatened by the presence of ash dieback. Symptoms of this disease are now showing throughout the PDNP and it is predicted to kill 60-90% of ash trees across the UK. Ravine woodlands with low diversity are especially vulnerable. The National Trust is currently removing infected ash trees that present a health and safety risk to the public at Dovedale and, along with Natural England, are increasing tree and shrub diversity in patches in Dale ash woodlands. Chatsworth Estate is also undertaking similar management measures. Increasing species diversity is an opportunity presented by ash dieback to make woodlands more resilient and biodiverse. It is of particular priority in areas where woodlands are currently ash dominated, and Natural England are progressing this work at Lathkill Dale.

Smaller fragmented woodlands across the PDNP are generally in poor condition. Many of these woodlands are lacking in species diversity due to past and present anthropogenic and browsing pressures – in particular, overgrazing by deer and sheep prevents regeneration of trees and ground flora. The structure and diversity of many woods has also been altered by Dutch elm disease over the last 50 years, impacting a range of species including the white-letter hairstreak butterfly which has lost much of its food source.

Invasive species are present in PDNP woodlands. Rhododendron in particular shades out the understorey and outcompetes many important species that contribute to the diversity and conservation value of the woodland. Non-native sycamore and beech regeneration is colonising some woodlands. However, these trees may become more desirable as fast growing replacements for ash trees lost to dieback, though this would be as part of a diverse mix with true natives such as lime, alder, and field maple.

Management of woodland sites has changed dramatically over the last few centuries. Traditional management techniques and practices such as coppicing and pollarding have largely ceased and some sites have been neglected. As a result the woodland structure has been completely altered. Some woodlands have very few veteran trees and deadwood left, which is now being addressed in some areas. Development such as housing and quarrying, and tourism have also altered sites due to the increase in disturbance and pollution. Lichen and bryophyte communities are strongly affected by air pollution in particular. Sulphur dioxide pollution has been dramatically reduced in recent decades allowing some of these species to recover. There are unknown impacts on woodlands from the use of agro-chemicals. These are potentially affecting important tree mycorrhizal relationships.

# What are the potential impacts of climate change?

| Overall potential impact rating |

# Invasive or other species interactions

Climate change has the potential to have a severe negative impact on PDNP woodland, both directly and indirectly. Woodlands are very sensitive to changes in precipitation and temperature that can not only stress the dominant tree species but also makes them more susceptible to disease and invasive species. As plant diseases (such as Phytophthora and ash dieback) become more prevalent they pose the biggest risk to the long-term health and diversity of woodlands. Key canopy species may be lost or severely reduced through both disease and extreme weather events, increasing the exposure of ground flora and potentially its vulnerability to drought and invasive species. Vernal ground flora such as wild garlic and bluebells are likely to be less at risk due to their shorter exposure period. Data Certainty: High

Flood events, predicted to increase with wetter winters, will facilitate the spread of invasive or nuisance plant species such as Himalayan balsam that threaten the understorey, with woodland near waterways most susceptible to invasion. Data Certainty: High Increased atmospheric carbon dioxide and nitrogen may increase plant growth rates allowing competitive species such as rhododendron to spread in the understorey. How much the community structure will change is unknown as all woodland species will likely experience faster growth. Data Certainty: Low Animals such as insects, deer, and grey squirrel are also a potential threat to stressed woodlands. Browsing of seeds and seedlings in particular may put some tree species at risk as they become unable to regenerate. Oak may be at an increased risk of decline from the wood boring beetle, the two spotted oak buprestid. It is possible that new pests and diseases may spread from the south.

# Direct impacts of climate change

Changes in temperature and precipitation that alter seasonal weather patterns could have a large impact on woodlands. Warmer winter temperatures could lead to: reduced vernalisation of fruit affecting seed viability, inadequate winter hardening leaving plants vulnerable to cold snaps, and advanced bud burst as warmer days arrive earlier. The species composition of woodlands may be altered especially where natural regeneration is reduced. There may also be a loss of mosses and bryophytes in some areas that have both warmer temperatures and reduced rainfall, followed by a shift in species to those that are better adapted to the conditions. Ash woods and oak woods on the edge of their range are particularly sensitive to a climate shift. Northern ash wood types with assemblages more similar to National Vegetation Community (NVC) W9 may become move towards south eastern W8 assemblages. The rare NVC W8g wood sage sub-community may be vulnerable to species composition changes. Characteristic PDNP oak wood communities with moss and lichen rich bilberry understories (NVC W16b) may be lost as they are replaced by assemblages more common in the south of England (more similar to NVC W16a) Data Certainty: High

Water table fluctuations, flooding, and drought all have an impact on plant root depth and distribution of species. Waterlogging is likely to restrict tree root depth for some species - leaving them more exposed to wind throw and drought. The stability of soils with long-term waterlogging may also be compromised. Periods of drought could affect plants with shallower roots, those on free-draining soils, and drought-sensitive tree species such as beech. In years of extreme drought tree mortality may be widespread leaving the woodland ground flora at greater risk too. As soil moisture profiles are altered there will likely be a shift in community composition that could convert dry woodlands into wet woodlands or vice versa. Data Certainty: High

Extreme events such as an increased frequency of wind throw and environmental stress are a threat for woodland plants, especially mature and veteran trees. Loss of older trees will also cause a loss of whole communities associated with them – specialist species such as fungi, lichen, and invertebrates. Conversely, some of these species may survive in deadwood or deadwood will act as a new habitat for other species to thrive in. Gaps in woodlands may be filled by pioneer tree species such as birch or rowan that could become more dominant in some areas. Such gaps, together with the impact of temperature rise, may also provide opportunities for colonisation by southerly insects such as silver-washed fritillary. Data Certainty: High

The growth rate of trees can be influenced by the carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere. With a predicted rise in carbon dioxide it is possible trees may experience increased productivity. Seedlings may grow quicker and leaf area could also increase. This will enhance natural regeneration and improve canopy resistance. However, woodlands with relatively open canopies could become more shaded, causing changes to the ground flora and possibly altering community composition. Data Certainty: Low

# Human behaviour change

Increased visitor numbers are expected in the PDNP, particularly in woodlands as people seek cooler places to walk on hot days. Bare ground may result where insufficient light is available through the canopy, or ruderal species such as nettles, thistles and other rank species may colonise in more open areas. This is also likely to impact animals, with disturbance causing changes to breeding and feeding patterns for birds and invertebrates. Data Certainty: High

Woodland creation and tree planting are likely to increase as part of climate change mitigation efforts. It is a popular carbon sequestration method that may benefit PDNP woodlands as their area of cover and connectivity can be enlarged and improved. Data Certainty: Moderate

# Nutrient changes or environmental contamination

Woodland plants are sensitive to changes in nutrient availability, both in the air and on the ground. Lichen and bryophyte communities are especially sensitive. Nitrogen deposition, a result of air pollution, can be particularly damaging. Data Certainty: Moderate Agricultural changes on adjacent land may also alter nutrient inputs which influence community composition and habitat structure. Ground flora is likely to be more affected than trees. Data Certainty: Low

# Other indirect climate change impacts

Hotter, drier summers are predicted to lead to an increased incidence of wildfire. Woodland flora and fauna are susceptible to damage and habitat loss. Broadleaved trees such as oak are highly resistant, but conifers, ground flora, and woodland understorey are more at risk. Conifer plantations next to moorland are the most at risk due to the level of dryness they could reach in summer when fire risks are highest and spread from moorland fires. The character and composition of woodlands may be altered as regeneration patterns change. This may also cause a loss of nesting and feeding habitat in some areas. Data Certainty: Moderate

# What is the adaptive capacity of woodlands?

Overall adaptive capacity rating |  |

While woodlands are a fragmented habitat type across the PDNP, the dominant tree species have a wide biogeographic range and there are a variety of management and restoration options available giving this habitat a moderate adaptive capacity within the PDNP.

In the Dark Peak and South West Peak, woodlands are largely confined to cloughs and gullies, while in the White Peak they are mostly confined to the dales. Under current land management regimes there is limited expansion potential into neighbouring areas. Adjoining land is often managed for sheep or grouse, or is valued for its own conservation characteristics. Due to spatial limitations, there are severe impediments to feature persistence and dispersal. Connectivity is variable and in areas that are highly fragmented the high edge to surface ratio increases woodland vulnerability to agricultural intensification. However, with increasing interest in increasing woodland and tree cover to benefit carbon storage, water quality, flood risk and biodiversity, there may be increased opportunities for some native woodland expansion beyond the existing cloughs, slopes, and dale brows. Data Certainty: High

Diverse mixed species woodlands have greater resistance to climate change stressors than single species woodlands. This is especially true with regards to disease or pest outbreaks that only affect one or two species such as ash or oak. Larger stands of woodland are also more resilient as they are able to maintain a cooler microclimate and have more stability in high winds. Deeper roots offer extra support in storm events and help stabilise soils that can otherwise be eroded by heavy rainfall. Wooded slopes help reduce flood risk for lower lying landscapes and in riparian areas can keep waterways cool which benefits fish and invertebrate populations. Areas such as the White Peak dales have been highlighted as climate refugia – where cooler woodlands provide shelter for other species within the landscape allowing them to persist longer in the changing climate. Data Certainty: High

Some environmental stewardship options are available for maintenance, restoration and creation of woodland. Where woodlands are on private land these schemes provide incentive for keeping woodlands in good condition. Most upland ash woods (84%) are protected within SSSI sites, as are many of the upland oak/birch woodlands. Good availability of financial resources and information means that management organisations are able to facilitate works to increase the resilience of woodland in the PDNP. One example is Moors for the Future Partnership and National Trust’s work on clough woodlands in the Dark Peak where the planting of a mixture of native trees is taking place. Data Certainty: High Policy or management actions may be undertaken to partially overcome or offset climate change stressors, by promoting structural and species diversity within existing woodlands and managing water across catchments. Data Certainty: Moderate

# Key adaptation recommendations for woodlands:

# Improve current condition to increase resilience

The current condition of a feature is an important factor alongside its sensitivity and exposure, in determining its vulnerability to climate change. These recommendations are aimed at improving the condition of the feature at present, therefore making it better able to withstand future changes to climate.

- Reduce grazing pressures where possible. Recognise the importance of an integrated deer management plan for the park.

- Encourage more continuous cover forestry – to maintain higher levels of carbon storage and decrease soil losses.

- Improve protection, management and recruitment of veteran trees.

- Consider water management in woodlands predicted to experience drought.

- Further study is required to explore appropriate opportunities for woodlands to be used in local wood fuel schemes.

- If visitor numbers increase at easy to access locations, encourage visitors to use alternative transport such as bikes and public transport to maintain tranquillity of the area.

- Consider the impact on key views when planning adaptations.

# Improve current condition to increase resilience: Increase structural diversity to improve resilience at a landscape scale

The current condition of a feature is an important factor alongside its sensitivity and exposure, in determining its vulnerability to climate change. These recommendations focus on increasing the structural diversity of the area or habitat in which the feature is found. This can help to offset the effects of climate change on the feature, as well as to allow it to be in a better position to recover from future climate changes.

- Increase diversity of tree species; especially in single species woodlands. Accept change in composition of woodlands, such as accepting species not previously native to the PDNP.

- Continue improving woodland condition – more native woodland creation, encourage regeneration to increase structural diversity, increase patch size (>2ha) to meet habitat requirements for birds and other species, increase decaying wood for replenishing soils.

- Natural woodland regeneration by excluding stock should be seen as preferable to tree establishment, with the latter principally to increase diversity - importance of scrub is underestimated.

- Convert small or unused conifer plantations to broadleaf/mixed woodlands.

- Increase establishment of field and boundary trees, particularly across the White Peak, to increase habitat diversity and connectivity, replace trees lost to Ash Dieback, enhance the landscape and provide shade and better grazing for livestock in hotter summer conditions.

# Adaptations that could aid other features

These recommendations are changes that could be made to this feature, which will have a positive impact on the ability of other vulnerable features to withstand future climate change.

- Increase connectivity between woodlands to provide wildlife corridors.

- Increase woodland cover – to keep waterways cool, provide shelter for other species as temperatures increase, increase carbon storage, and improve water quality.