Feature Assessment: Watercourses, ponds and reservoirs / Dew ponds and other ponds

# Dew ponds and other ponds

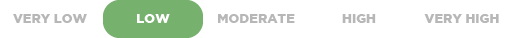

| Overall vulnerability |  |

# Feature(s) assessed:

- Dew ponds and other ponds

# Special qualities:

- Internationally important and locally distinctive wildlife and habitats

- Landscapes that tell a story of thousands of years of people, farming and industry

# Feature description:

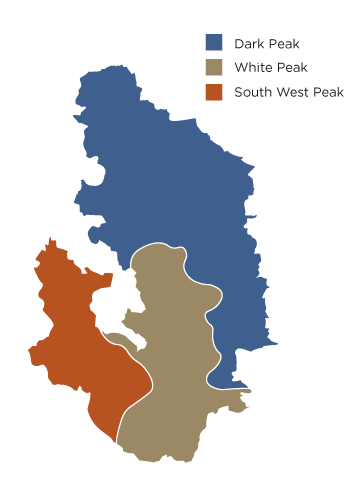

This feature is predominately found in the White Peak, but can also be found in much smaller numbers in both the Dark Peak and South West Peak. There has been a significant loss of ponds in the PDNP and across the UK. The White Peak has the majority of the remaining ponds, the Dark Peak having significantly fewer and the South West Peak least of all.

Dew ponds are human-made and were usually created to help provide water for livestock. In the White Peak many of the ponds were created in the 19th century and give an insight into farming in the area. These circular ponds were lined with lime and clay. Cobbles were often placed on the surface to create a durable surface. Many dew ponds were re-lined with concrete in the 20th century.

Other types of ponds included within this feature are those associated with mills and village ponds.

Within the PDNP 401 ponds are recorded as of being high value and classed as priority habitat, primarily due to the presence of priority amphibians – toad and great crested newt. Half of the world’s population of great crested newts are found within the UK and ponds are a key habitat for this species. The network of dew ponds in the White Peak holds a nationally important population of great crested newts. Ponds also provide a habitat for aquatic invertebrates.

# How vulnerable are dew ponds and other ponds?

Dew ponds and other ponds in the PDNP have been rated ‘very high’ on our vulnerability scale. This score is due to high sensitivity and exposure to climate change variables, coupled with a poor current condition, and a low adaptive capacity.

Extreme events including flood and drought could have a significant impact on this feature, reducing their functionality and potentially leading to ponds being abandoned or infilled. Dew ponds with intact historic surfaces (clay and cobbles) are becoming increasingly rare. The adaptive capacity of this feature is low as there are a limited number that are functional. PDNPA funding is currently available for pond restoration, but this is very limited.

# Current condition:

Dew ponds and other ponds are viewed as vulnerable, particularly those found in the White Peak. Surveys suggest there was a significant reduction in their number, potentially up to 50%, in the 1970s and early 1980s. More recent studies have seen the number of ponds continue to decline but at a slower rate. In the South West Peak and Dark Peak the figures have remained relatively stable, however the information available on their current condition is limited. It is also not known how many new ponds have been created in gardens or schools.

There is a wide variation in the habitats provided by ponds which is due to the individual water quality, depth and chemistry having a significant impact on the plants it supports. The type of vegetation and its coverage in each pond helps to determine the range of aquatic invertebrates found. Populations of several nationally scarce water beetles and the great crested newt make this PDNP habitat even more important. Several locally rare plants such as common water-crowfoot, pond water-crowfoot and marsh cinquefoil can also be found at certain locations.

Changes in water quality have seen a negative impact on ponds. For example run-off from the surrounding areas can cause fertiliser, slurry and herbicides issues in ponds. If the levels of nutrients and minerals increase it can lead to an excessive growth of algae reducing the amount of oxygen found in the water, impacting the habitat considerably.

Intensive management of farmland that surrounds dew ponds can also damage ponds lined with clay if trampled by heavy livestock. Management can also alter the surrounding habitats which some pond species rely on.

The dew ponds of the White Peak have been particularly vulnerable to neglect, leading to infilling as well as abandonment when no longer needed. The clay or concrete linings can crack if not maintained which removes the functionality of the pond. In addition, the re-lining of dew ponds with concrete, whilst effective for water retention, can mask or destroy the historic pond lining, altering its character significantly.

# What are the potential impacts of climate change?

| Overall potential impact rating |

# Nutrient changes or environmental contamination

Increased levels of nitrogen and carbon dioxide could have a significant impact on the water quality and its chemistry, affecting the growth rates of pond vegetation. A rise in nutrients in water can lead to excessive growth of algae reducing the amount of oxygen and affecting invertebrates. Algal blooms could change the whole community structure and function of a pond. Data Certainty: Moderate

Higher average temperatures leading to longer growing seasons could also affect the balance of nutrients and plankton in pond ecosystems. This could affect a number of groups such as diatoms, desmids and zoo plankton, which could then affect macroinvertebrates and other species all the way up the food chain. It may be that phytoplankton blooms start earlier and last longer which would have knock-on effects through the food chain. There could be a decrease in light penetration because of increased phytoplankton, as well as competition for carbon dioxide and lower oxygen levels as phytoplankton decompose. These could all lead to a loss of fish and other animals. Data Certainty: Moderate

If the frequency of storms increases there could be increased run-off leading to eutrophication, impacting the ecosystem of the pond. Standing water is highly sensitive to changes in the amount of sediment and nutrients. Data Certainty: Moderate Any reduction in ’flushing’ during drier summers may see concentrations of nutrients increase. If these changes cause a rise in algae growth it may be difficult for ponds to recover. Wetter winters may help to counteract the impacts of drier summers, but dew ponds are less dependent on this process as they usually don’t overflow very much. Data Certainty: Low

A rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide could result in acidification of water through the dissolution of carbon dioxide which makes carbonic acid, although the impact should be reduced in ponds lined with concrete or limestone due to their high alkaline content. Data Certainty: Moderate

# Human behaviour change

Ponds have already been damaged by livestock and this could worsen if grazing levels increase due to climate impacts. Changes in agricultural economics and increased availability of piped water could see ponds abandoned or infilled. Data Certainty: Moderate

Ponds are sensitive to changes in the surrounding area caused by droughts or floods. For example dew ponds may no longer be maintained in areas no longer suitable for livestock. Conversely natural ponds may benefit from increased shading if land is abandoned. Data Certainty: Moderate

Direct impacts of climate change Increased average temperatures and longer growing seasons could result in lower dissolved oxygen levels in ponds. It may be that the interface between water and the sediment layer becomes deoxygenated although this effect may be limited to shallower ponds. Data Certainty: Moderate

If ponds dry up earlier in the year during drier summers, amphibians may not have time to complete their lifecycle. Phosphorous may be released from sediment due to the temperature dependency of nutrient-cycling rates in the sediment, increasing eutrophication risk. As a result, some invertebrates and fish may be unable to survive. Data Certainty: Moderate

Dew ponds, especially those located on hill tops, rely entirely on rainfall and run-off from a small surrounding catchment. Drier summers and drought could therefore have a significant impact. Long vegetation around the edge of a pond can impact evaporation rates, often decreasing it due to shading the water but sometimes increasing it. Drought may restrict vegetation growth, which would alter this interaction. Data Certainty: Moderate

An additional potential impact of drought is that stream-fed ponds may lose connection with other water bodies for part of the year. Ponds can dry out completely early in the year, losing their function as permanent ponds. Some pond species can adapt by moving to other ponds, or survive as eggs or in other life stages in mud. However, if multiple ponds dry out then species could potentially be lost. Dead vegetation from the pond drying out may add organic matter and nutrients, increasing the chances of infill. Extreme drought conditions could also crack pond linings. Data Certainty: Moderate

An increase in how often ponds dry out or see water levels drop, can stress plants and animals – making them unsuitable as habitats. PDNP dew ponds provide internationally important breeding grounds for the great crested newt, so any change could have a significant impact on numbers. As great crested newts only travel a limited distance from their birth ponds, landscape connectivity is very important. Data Certainty: Moderate

If clay-lined dew ponds are subject to greater extremes of temperature, or prolonged periods of dry weather, they could suffer from freeze/thaw action or cracking, reducing their water retaining capacity, and making them more likely to be re-lined with concrete. Data Certainty: Moderate

# Invasive or other species interactions

A rise in average annual temperatures could see a further increase in non-native plants such as Australian swamp stonecrop or Canadian pondweed. If native species are outcompeted, the biodiversity of the pond may decrease affecting plant and animal communities. Submerged species may be replaced by floating or evergreen species. Data Certainty: Moderate

# Sedimentation or erosion

Wetter winters leading to increased flooding could impact marginal vegetation, which can be sensitive to erosion. Flooding could affect the stability of banks and lead to an increase in nutrient levels within the pond. Data Certainty: High

An increase in storm events could cause more sediment to reach ponds, as well as nutrients from run-off such as fertiliser applied to the surrounding land. Data Certainty: Low

# What is the adaptive capacity of dew ponds and other ponds?

Overall adaptive capacity rating |  |

There are many ponds within the PDNP however only a small number are functional as few have been maintained or restored. The ponds are well dispersed and a more resilient network could be created if more were restored. Data Certainty: Very High

Some of the important species associated with PDNP ponds, for example the great crested newt, have limited dispersal capacity. There are large distances of inhospitable habitat in between many ponds that can affect amphibians, particularly those that are less able to disperse. Pond invertebrates however seem to be better at dispersing than invertebrates in other habitats, as ponds have always been separated in the landscape. This increases the adaptive capacity of this aspect of ponds as a habitat. Data Certainty: Very High

Recovery of climate-affected ponds could be limited by species capabilities and dispersal. Some ponds may have dried out during hot summers or others lose nutrients or sediments from increased storm events. Some species can benefit from seasonal drying of ponds but this may not work if ponds dry out for longer periods. Species without these survival strategies for dry periods could have nowhere to go. The fragmented nature of the habitat means the potential for re-colonisation from other ponds is limited, so once these species are lost the ponds may not recover. Data Certainty: Moderate PDNPA grants are available for pond restoration, but are very limited. It is not currently possible to implement adaptation for ponds under agri-environment schemes, as current agri-environment schemes do not fund restoration of man-made structures such as dew ponds. Data Certainty: High Many dew ponds are under the management of nature conservation organisations such as those within National Nature Reserves and County Wildlife Trust land. This may help to protect these dew ponds more than others in the PDNP. Data Certainty: Low

# Key adaptation recommendations for dew ponds and other ponds:

# Improve current condition to increase resilience

The current condition of a feature is an important factor alongside its sensitivity and exposure, in determining its vulnerability to climate change. These recommendations are aimed at improving the condition of the feature at present, therefore making it better able to withstand future changes to climate.

- Maintain and enhance existing sites, where possible, consider re-lining failing ponds with materials that reflect their historic character.

- Reduce non-climatic sources of harm such as non-native species and nutrient sources.

- Minimise agricultural inputs, especially slurry, fertilisers and pesticides. Give consideration to good management of waste to improve catchment quality, including effective slurry store management.

- Manage biosecurity to limit spread of invasive and non-native species.

- Investigate external funding sources for a major pond project using citizen science.

- Create semi-natural vegetation such as woodland along run-off pathways to reduce evaporation and maintain water quality.

- Keep a strategy for dewpond restoration under review, due to their high vulnerability and extensive cost input required.

- Liaise with other protected landscapes to share knowledge and management techniques.

# Adaptations that could aid other features

These recommendations are changes that could be made to this feature, which will have a positive impact on the ability of other vulnerable features to withstand future climate change.

- Restore key sites to link clusters and improve pond connectivity for species such as great crested newt.