Feature Assessment: Wildlife / Curler

# Curlew

| Overall vulnerability |  |

# Feature assessed:

- Curlew (Numenius arquata)

# Special qualities:

- Internationally important and locally distinctive wildlife and habitats

# Feature description:

The curlew is the largest of the Britain’s wading birds and is easily recognised by its distinctive down curved bill, long legs and brown barred and streaked plumage. The atmospheric bubbling call of this ground-nesting bird is highly evocative of the PDNP bogs and moorland, where curlew currently return each spring to breed. PDNP birds are internationally significant, as an estimated 2% of the UK population is found here, with the UK population being around 25% of the global total.

# How vulnerable are curlew?

Curlews in the PDNP have been rated ‘very high’ on our vulnerability scale. This score is due to high sensitivity and exposure to climate change variables, but a low adaptive capacity – despite the currently moderately positive trends in the PDNP compared to the national picture.

Curlew populations in the PDNP are reduced from their historical numbers, but recent data suggests they may be recovering. Climate change is likely to have the greatest impact on curlews in their wintering grounds outside the PDNP through sea level rise and flood defence construction. Within the PDNP, effects on soil invertebrate populations are expected to have the greatest impact. As long-lived and site faithful birds, curlew are not very adaptable. Modelling shows curlew moving north and west out of the PDNP by the end of the century, if they still survive locally. Support from organisations and schemes operating in the PDNP go some way to support their conservation, but more could be done.

# Current condition:

The overall UK curlew population is in rapid decline, showing one of the biggest declines across the bird’s worldwide range. In fact, the UK may account for the biggest impact on the global population of any country.

The reasons for the national decline are many and varied. Past drying of peat soils through drainage, burning and wildfires; high rates of human disturbance; destruction of nests through agricultural activity; deterioration of agricultural soils; and a lack of breeding success due to high numbers of generalist predators are all thought to have contributed.

Population trends in the PDNP are less well known and probably vary from site to site. The 2004 Moorland Breeding Bird Survey found an increase in curlew pairs since 1990 across the PDNP. Local data from the Eastern Moors shows that curlew populations are stable or increasing. However, curlew may already be suffering some effects of climate change, as populations have contracted significantly upwards in elevation in recent years. Curlew also appear to be wintering closer to their breeding grounds due to milder winter conditions.

# # What are the potential impacts of climate change?

| Overall potential impact rating |

# Direct impacts of climate change

Losses of wintering grounds due to sea level rise may have drastic effects on curlew populations. Most curlew winter on estuarine mud flats. These are at risk of loss to rising seas, compounded by erosion and human developments. Reduction in the height of intertidal patches is predicted to cause reduced survival rates, with a 40 cm loss eliminating survival. Many estuaries are bounded by human developments and sea defences, so habitat will be reduced. Invertebrate availability and curlew feeding time will likely be reduced as a result. This will result in fewer birds returning to the PDNP to breed, and those returning being in worse condition. Data Certainty: Very High

In the PDNP, drier summers and extreme events such as droughts may lead to an impenetrable ground surface and invertebrates moving deeper into the soil. This would cause a reduction in invertebrate availability for both adults and chicks, particularly in peatland habitats such as blanket bog or wetter pastures. Drier conditions due to a changing climate or drying of agricultural soils are thought to be the cause of the observed upward shift in curlew altitude. This may continue with drier summers, driving curlew from lowland pastoral sites. Increased annual average temperatures may also have an effect. Cranefly larvae living on the soil surface, which are a major food source for curlew and other moorland waders, are killed off by high temperatures and extreme dry conditions such as those seen in drought. Data Certainty: Moderate

Curlew migration timings may be affected by warmer winters and springs. Similarly, the reproductive cycle of marine invertebrates upon which curlew rely during the winter may be disrupted. Curlews and invertebrate prey may become mismatched, reducing resource availability for overwintering birds. Additionally, it is not known whether these marine invertebrate populations will be able to adapt quickly enough to changing conditions to survive in some locations, further reducing availability at some wintering sites. These effects combined would mean reduced curlew fitness upon migration, and so fewer birds surviving the return journey. However, increasing numbers of curlews are wintering close to or at their breeding grounds, meaning that PDNP curlews may decrease migration as conditions change. Data Certainty: Moderate

# Human behaviour change

Climate change is likely to lead to increased construction to combat its effects, from renewable energy sources such as wind turbines to sea defences to combat sea level rise. The effect of upland wind farms on breeding bird densities is disputed, and the PDNP’s status as a National Park will be likely to help protect PDNP curlew populations, though migration routes may be affected Data Certainty: Low However, there is limited protection for many wintering grounds. An increase in offshore or nearshore wind could reduce curlew numbers. Tidal barrage construction to generate renewable energy may reduce curlew density significantly, though the effect is not well studied. Habitat may also be lost to hard flood defences, which become a barrier to movement as sea level rises. Managed realignment of the sea could put pressure on wintering curlew to adapt to habitat changes, though may provide opportunities through habitat creation. Data Certainty: High

Inland, upland forest establishment may too prove damaging to curlew populations. Some curlew declines have been strongly associated with an increase in surrounding woodland. Woodland establishment for carbon offsetting and flood management could affect PDNP curlew populations. Data Certainty: High

An increase in visitors due to hotter drier summer conditions may increase disturbance. Curlews are known to be highly sensitive and visitor pressure has been associated with the absence of breeding curlew on South Pennine uplands. Land use changes will also affect curlew populations. Some land may be abandoned as ground conditions change leading to afforestation, removing curlew habitat. Data Certainty: High Changes to the economics of grouse moor management due to altered moorland conditions may have negative effects on curlew. Changes in the climatic conditions of heather moorland could lead to some sites being abandoned as uneconomic, while intensive management may increase on others to offset these changes. Loss of predator control would have a negative effect on curlew nesting success, at least in the short term, due to predation. Conversely, an increase in burning management could cause a reduction in curlew populations. Data Certainty: Low

# Invasive or other species interactions

Increased annual average temperatures may have diverse negative effects on curlew through their interactions with other species. Warmer winters could raise survival rates of generalist predators such as foxes and carrion crows, leading to increased nest predation in the spring. Higher temperatures may also increase the prevalence of parasites on curlew. Although parasite effects on the host are not well understood, a greater parasite load is likely to be detrimental to curlew fitness and fecundity. Finally, warmer spring temperatures can promote green algae growth in estuarine wintering grounds. Algal mats negatively affect marine invertebrate abundance, reducing food availability for wintering curlew and lowering their migration fitness. Data Certainty: Low

An increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide, combined with increased nitrogen deposition from winter rainfall may act to increase plant growth rates. This could negatively affect curlew nesting, as an increase in sward height would reduce visibility, an important feature in curlew nest choice. Young birds choosing a nest site would have more limited options, and those birds already faithful to a nest site would be more vulnerable to predation. Higher plant growth rates may also encourage scrub encroachment in low grazing areas, reducing curlew habitat. Data Certainty: Moderate Nutrient changes or environmental contamination

Changes in annual precipitation cycles could negatively affect curlews through altered nutrient status of their habitat. Wetter winters and drier summers may affect wetter sites such as bogs and wet flushes that are preferred for curlew feeding. Higher flows in winter may cause flushing of nutrients from the system. Altered nutrient status can change invertebrate abundance and community composition, limiting food resource for curlew. Data Certainty: Low

# Sedimentation or erosion

An increase in the frequency and severity of storms and droughts may act to increase erosion on curlew habitat. As many curlew nest on the fragile peatlands of the PDNP, this could have severe consequences. Further drying and loss of peat would reduce available habitat and cause deterioration in the condition of existing habitat. Invertebrate availability declines relative to peat condition, reducing fitness of curlew on degraded habitats. Data Certainty: Low

# Other indirect climate change impacts

Hotter drier spring and summer conditions may increase curlew losses to wildfire. Increased frequency and severity of wildfire would increase nesting losses in ground nesting birds and cause habitat loss on open moorland. Because curlew are site faithful, re-nesting after large-scale wildfires may be unlikely, though post-restoration habitat may become available. Data Certainty: Low

# What is the adaptive capacity of curlew?

Overall adaptive capacity rating |  |

Suitable curlew habitat is increasingly fragmented within the PDNP, with large areas of unsuitable moorland and pastureland separating good habitat. Curlew are generally faithful to a nesting site, and young tend to nest near their hatching location, so population expansion and movement is slow. There are few other barriers to movement, so curlew populations are able to adapt to changing conditions if they are not too rapid. Modelling shows curlew moving north and west out of the PDNP by the end of the century, if they still survive locally. Data Certainty: High

Curlew can recover from significant losses if the conditions are right. Dispersal is relatively good albeit slow, so adjacent populations can replace those lost. However, their behaviour is not likely to be flexible, and their evolutionary potential to adapt is low. This is due to their long lifespan with a slow maturity to breeding age, combined with small clutch sizes. Data Certainty: Moderate Their status as a specialist with specific requirements for both summer breeding and wintering conditions may limit their adaptability. Data Certainty: Very High

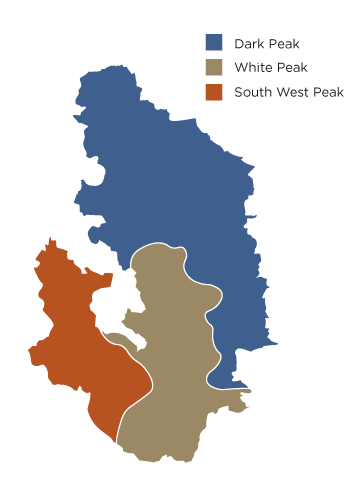

Some money is available for curlew conservation in the PDNP. Many agri-environment schemes focus on farmland waders including curlew. These schemes have been shown to be effective for farmland birds across Europe, or at worst not harmful. However, it is questionable whether these schemes are effectively implemented, and there is uncertainty over the future due to exit from the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and other changes in land policy. Data Certainty: Low Institutional support could assist curlew climate change resilience. Projects such as the RSPB Curlew Recovery Programme and the South West Peak Partnership Working for Waders aim to implement and assess management interventions to promote curlew recovery, and therefore climate change resilience. However, serious management interventions on land not specifically used for nature conservation are more difficult to achieve. Much of curlew habitat in the PDNP is covered by Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) or Special Area of Conservation (SAC) designation, with curlew mentioned as a reason for citation in the Dark Peak SSSI. These designations have been shown to have a positive correlation with curlew densities. Curlew are also a red listed species in the UK, giving them some conservation priority. Data Certainty: Moderate

Management for curlew is reasonably well known. Moorland rewetting is being implemented across the Dark and South West Peak, and can improve curlew habitat by increasing vegetation heterogeneity and abundance of their invertebrate prey. However, drain blockage benefits fly larvae most, which form a lower proportion of curlew diet than in other waders. As a result, curlew may not benefit from rewetting as much as other species. More research is required to understand which management techniques are the most effective and how curlew interact with their habitat, climate, and other species. Data Certainty: Moderate

# Key adaptation recommendations for curlew:

# Improve current condition to increase resilience

The current condition of a feature is an important factor alongside its sensitivity and exposure, in determining its vulnerability to climate change. These recommendations are aimed at improving the condition of the feature at present, therefore making it better able to withstand future changes to climate.

- Create or back experiments to test the effectiveness of current and potential management techniques.

- Improve curlew habitat and increase connectivity through management.

- Ensure silage cutting is delayed until after chicks have left the nest.

- Cease the ploughing of fields and reduce chemical inputs to improve soil invertebrate populations.

- Maintaining sward lengths above minimum can reduce predation risk and can mean less predator control is needed.

- Rush management should be planned with the needs of different species in mind, some suitable areas of long rushes should be left intact.

- Predator control could be a useful tool in high predator density areas, but may inadvertently increase predator populations and disrupt other species interactions. Research is needed to determine if a more natural system would be a better option for the future.

- Further study is needed to track how productivity and breeding success are changing with climate. Recording of clutch sizes at nest can help.

- Encourage further uptake of environmental land management schemes by farmers within the PDNP.

# Improve current condition to increase resilience: Targeted conservation efforts for important sites and at risk areas

The current condition of a feature is an important factor alongside its sensitivity and exposure, in determining its vulnerability to climate change. These recommendations are conservation measures aimed at those sites that will have the biggest impact for this feature – either because they are particularly important for the feature or because they are most at risk from climate change.

- Wetland restoration should be a priority. This is both through upland rewetting and lowland drain blocking.

- Develop fire contingency plans, and ensure management of habitats reduces fire risk e.g. rewetting and increasing species or structural diversity. Influence visitor and behaviour management plans and practices to minimise ignition risk.

# Adapt land use for future conditions

These recommendations are adaptations to the way in which people use the land. Flexibility in land management - reacting to or pre-empting changes caused by the future climate - should afford this feature a better chance of persisting.

- Reduction of soil compaction will reduce surface drying and increase habitat suitability for curlew.

- Reduce high grazing levels and avoid intensification of farming methods.