Feature Assessment: Wildlife / Great crested newt

# Great crested newt

| Overall vulnerability |  |

# Feature assessed:

- Great crested newt (Triturus cristatus)

# Special qualities:

- Internationally important and locally distinctive wildlife and habitats

# Feature description:

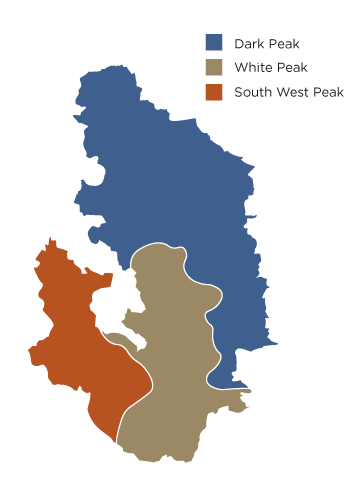

The great crested newt is the UK’s largest newt. It is easily recognised by its distinctive bright orange underside covered in irregular black blotches and the large crest along the backs of males in spring. Found throughout the White Peak and in some parts of the Dark and South-West Peak, they utilise both terrestrial and aquatic habitats during their lifecycle. Ponds are a key habitat feature needed for breeding. The UK may hold up to 50% of the global population, so healthy populations in White Peak dewponds could be of high importance.

# How vulnerable are great crested newts?

Great crested newts in the PDNP have been rated ‘high’ on our vulnerability scale. This score is due to high sensitivity and exposure to climate change variables, coupled with a poor current condition, and a moderate adaptive capacity.

The PDNP great crested newt population appears to be stable, having recovered from heavy historical declines. Terrestrial and aquatic habitats are both essential for the survival of this species, with ponds being most at risk in the face of climate change. Their longevity and the existence of metapopulations give this species some adaptability. However much depends on land management decisions and ongoing maintenance of ponds.

# Current condition:

The PDNP great crested newt population suffered a severe decline between the 1960s and 1990s. Loss of breeding ponds and intensification of agricultural practices are reported as the main drivers. Some of this damage has since been reversed by a number of pond projects carried out by the PDNPA between 2004 and 2011. As great crested newt survival depends on metapopulations, these projects focussed on restoring key ponds in clusters and ponds that helped link neighbouring clusters together. Few individual ponds support large numbers of newts but each pond plays an important role in maintaining the overall population. The PNDP great crested newt population is now thought to be reasonably stable but may suffer further declines if pond restoration slows and ponds are lost.

Great crested newts are able to utilise ponds of varying condition but can be sensitive to water quality changes. They can tolerate poor water quality for short periods providing the pond has sufficient oxygen levels, and in the case of breeding ponds, contains enough plants suitable for egg laying. Particularly in areas of intensive management, ponds have been contaminated by fertiliser, slurry and herbicide application. Where this has occurred in large amounts, eutrophication has diminished the usability of this aquatic habitat. Silting up has also rendered some ponds unusable when water levels are reduced.

Land management and development continues to threaten great crested newts in the PDNP. Dewponds are susceptible to infilling as well as neglect which has led to pond loss as linings are damaged by drought or freezing. Clay or concrete linings may also be cracked by heavy livestock. Intensive farming practices have led to loss of terrestrial habitat used by newts. Where impacts on great crested newts are unavoidable, mitigation is usually carried out. They generally do well as a pioneer species in newly created habitat but long-term survival rates at receptor sites is largely unknown.

Other risk factors are predation and disease. In the aquatic habitat, they are often eaten at the egg-larvae stage by invertebrates, but introduction of fish, including stickleback, can result in loss of breeding success in ponds. In terrestrial habitat, they can be predated on by animals such as foxes, badgers, rats, and hedgehogs. Birds are known predators in both aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Diseases caused by pathogens such as ranavirus and chytrid fungi pose an unknown level of risk to great crested newts.

# What are the potential impacts of climate change?

| Overall potential impact rating |

# Direct impacts of climate change

Pond habitat, essential for great crested newt breeding, is highly susceptible to changes in precipitation. Decreased rainfall and drought that is predicted to occur with hotter, drier summers is likely to affect the water levels in ponds and their suitability as habitat. Dewponds in the White Peak are particularly vulnerable, as these are shallow and depend on rainfall and run-off. Some ponds may become more seasonal, with drought periods increasing the chances of cracking the lining. Eutrophication could also increase. Loss of breeding ponds, particularly in summer when adult newts and larvae are using them, would lead to population decline. Data Certainty: High

Extreme events including heavy rainfall and drought could affect great crested newts year-round in both their aquatic and terrestrial habitats. One study of great crested newts in south-east England found that heavy rainfall events in winter led to low annual survival rates. During drought periods, great crested newts are at risk of desiccation if water or shelter are unavailable. Loss of individuals throughout the year is likely to result in population decline, especially in areas with smaller metapopulations. Data Certainty: Moderate

Timing of migration from terrestrial habitat to breeding ponds has been linked to temperature. Great crested newts need night temperatures to be regularly above 4°C or 5°C and it appears that maximum temperature throughout winter also plays in role in determining pond arrival times. Later arrival at breeding sites has been recorded in Kent associated with increasing temperatures over several years. This later migration means that juvenile feeding times may be shortened, and ponds are at an increased risk of drying up before the juveniles are ready to leave the pond, causing accelerated development or fatality. Hotter summers and warmer winters with increased temperatures are likely to affect migration and could severely affect their ability of great crested newts to complete their life cycle. Data Certainty: Moderate

Increased carbon dioxide levels and annual average temperatures may lead to increased plant growth rate, both on land and in ponds. Vegetation growth on land could provide additional shelter to help offset hotter summer temperatures and reduce desiccation risk. In ponds, vegetation growth may also provide additional cover and material for egg-laying. In some ponds this may lead to increased breeding success, however in other ponds, excessive plant growth may reduce space for courtship displays or be unsuitable for egg laying. Data Certainty: Low

One climate change model found that in a low emissions scenario, great crested newt populations would remain relatively stable. However, a high emissions scenario could cause widespread population losses with only limited sites of suitable climate space remaining. Data Certainty: Moderate

# Nutrient changes or environmental contamination

Great crested newts are sensitive to water quality changes. Extreme weather events, such as heavy rainfall, are likely to impact the nutrient loading of this habitat as increased run-off enters the pond. Eutrophication of some ponds is likely to occur causing a decline in the number of plants and animals that can survive there. Contaminated breeding ponds could cause severe population decline. Data Certainty: High

Decreased rainfall in summer could also cause problems. Lower water levels will change the dilution of nitrates and other nutrients, which can affect great crested newt breeding success. Lower nitrate level ponds are essential for breeding. Ponds with a high abundance of aquatic plants that are surrounded by low intensity farming will be less vulnerable to eutrophication than ponds with few plants and high levels of nutrient input. Areas with fewer low nutrient ponds may see breeding success decrease. Data Certainty: Moderate

Increased levels of carbon dioxide could cause the acidification of some ponds. Changes to water chemistry are most likely to happen to smaller or shallower ponds, with eutrophication being a major threat. Some pond habitat may be affecting localised populations. Data Certainty: Low

# Invasive or other species interactions

Aquatic habitats are particularly vulnerable to non-native invasive plants such as New Zealand pigmyweed and Canadian pondweed. With warmer temperatures predicted year-round, these plants are likely to have a longer growing season and may spread more easily as people transport them between water bodies. Although invasive plants are known to displace key plant species that are important for great crested newt egg-laying, one study found that great crested newts were unaffected by New Zealand pigmyweed. However, changes to water oxygen levels and loss of open spaces for courtship displays may still affect great crested newts at some sites. Data Certainty: High

Increased annual average temperatures may cause diseases such as the fatal ranavirus to become more prevalent in PDNP great crested newt populations. Research has shown that ranavirus incidence dramatically increases when temperatures rise above 16° Celsius. As these temperatures become more common, outbreaks of ranavirus will be likely to increase in frequency. Data Certainty: High

# Human behaviour change

Great crested newts are sensitive to disturbance in both terrestrial and aquatic habitats. Increased visitor numbers are expected during hotter, drier summers and great crested newt habitat may be more frequently disturbed. Human activity around ponds is likely to damage terrestrial habitat and disturb great crested newts while they are resting. Disturbance by dogs and livestock may occur on land or in ponds themselves. Data Certainty: Moderate

Land use changes and management decisions associated with climate change will continue to impact great crested newts and their habitats. Intensive farming with higher stock numbers could disturb great crested newts and damage both ponds and terrestrial habitat. Conversion to arable could cause fertilisers to enter the water course and cause eutrophication. Where areas of land are abandoned, great crested newts will probably do well as they are good pioneers. Most ponds on the other hand, require active management to remain suitable habitat for great crested newts. Data Certainty: Moderate Sedimentation or erosion

Wetter winters, drier summers and extreme events are expected to increase transport of sediment into ponds. Water quality may decrease, and ponds are likely to get shallower as they silt up. As a result, great crested newt pond habitat may be reduced in some areas. Data Certainty: Low

# Other indirect climate change impacts

Warmer winters may increase foraging opportunities. Due to the cold, newts normally enter a period of low activity during winter. However, they can emerge and forage on warmer days. This may become more frequent, and it is possible that some positive effects will occur across some populations. However, warmer winter temperatures may cause higher metabolic rates in hibernating newts, resulting in lower body mass in the spring which can cause fewer eggs to be laid. Data Certainty: Low

# What is the adaptive capacity of great crested newts?

Overall adaptive capacity rating |  |

Great crested newts depend on both terrestrial and aquatic habitats. A network of ponds with good connectivity and suitable terrestrial cover in between is important for the whole metapopulation. The water quality of breeding ponds is vital for maintaining populations, however great crested newts seem to be able to cope with a wide variation of water quality across their wider habitat. Great crested newts usually only migrate between 250 to 500 m but can disperse as colonisers up to a kilometre away. If other suitable habitat is identified beyond this range, then translocation is an option. Data Certainty: High

A relatively long-lived species, reaching up to 14 years in the wild, great crested newt populations can overcome poor breeding years. They can be resilient to the loss or damage of a few ponds as they move to other sites within their network. Adult diet is varied, and this increases their adaptive capacity. However, juveniles are limited to the food available in their natal pond. Data Certainty: Moderate

Environmental land management schemes and pond-oriented projects provide some funding for maintaining, restoring or creating great crested newt habitat. In the White Peak, the ‘Proliferating Ponds in the Peak’ project has helped to enhance a number of dewponds for great crested newts. There is potential for additional habitat to be created under the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA’s) Farming and Forestry Improvement scheme that helps with on-farm reservoirs. Funding is limited however, and it is likely that some ponds will be lost if pond restoration comes to a standstill. Pond availability and quality is a limiting factor for great crested newt populations and continual enhancement of this habitat is necessary to maintain and improve newt numbers. Loss of ponds could lead to the loss of a large number of great crested newts and population decline. Data Certainty: Moderate

Great crested newts are protected under the Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006 and a European Protected Species, which gives full protection under The Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017. Data Certainty: High A range of habitat management and restoration techniques, along with translocation guidelines are available from Froglife and other organisations. More research may be needed into techniques that offset climate change stressors. Data Certainty: Moderate

# Key adaptation recommendations for great crested newts:

# Improve current condition to increase resilience

The current condition of a feature is an important factor alongside its sensitivity and exposure, in determining its vulnerability to climate change. These recommendations are aimed at improving the condition of the feature at present, therefore making it better able to withstand future changes to climate.

- Minimise agricultural inputs to ponds, especially slurry, fertilisers and pesticides. Give consideration to good management of waste to improve catchment quality, including effective slurry store management.

- Systematically monitor invasive species in ponds, and control them where needed.

- Increase the use of sustainable drainage schemes for new developments.

- Translocate to new sites if needed. Undertake further research into translocation feasibility and sustainability.

- Encourage further uptake of environmental land management schemes by farmers within the PDNP.

# Improve current condition to increase resilience: Targeted conservation efforts for important sites and at risk areas

The current condition of a feature is an important factor alongside its sensitivity and exposure, in determining its vulnerability to climate change. These recommendations are conservation measures aimed at those sites that will have the biggest impact for this feature – either because they are particularly important for the feature or because they are most at risk from climate change.

- Continue restoring and creating ponds across the PDNP: make it a priority especially near existing populations such as in the White Peak.

- Improve habitat between ponds to help connect them. Focus on terrestrial habitat vegetation and inter-pond distances.

- Monitor existing populations. Records of population size and habitat quality will be important to inform adaptation planning.

- Protect potential new habitat as well as existing habitat that is impacted through development proposals, particularly where it is near existing populations.

← Golden plover Lapwing →