An inspiring space for escape, adventure, discovery and quiet reflection

# Transport & The Environment

Road transport is one of the biggest emitters of greenhouse gas emissions such as carbon dioxide, which contribute to climate change. In turn, climate change impacts the weather, which is already affecting travel within the Peak District National Park. The sustainability of road transport is likely to improve in the future with developments such as electric vehicles infrastructure.

Other factors affecting transport through the Peak District include developments outside the National Park, which can affect the volume of traffic.

# Impact of Transport on the Peak District’s Environment

# Climate Change

Road transport is by far the biggest emitter of carbon dioxide (CO2) within the Peak District National Park, accounting for 62% of all carbon emissions and 31% of all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (excluding point sources).

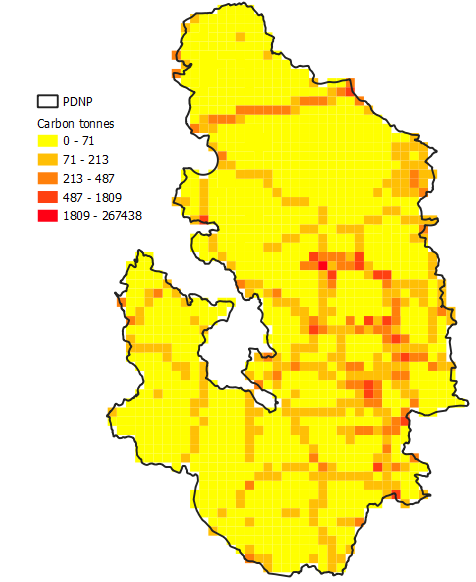

Looking at the carbon emissions map of the Peak District (see map below), the A Road network is clearly visible, in particular the ‘hotspot’ sites of Castleton, Bakewell and Baslow and several roads such as the A628 Woodhead Pass road that cuts through the Dark Peak in the north.

1x1 Carbon Emissions Map, Peak District National Park 2019.

GHG emissions from road transport made up around a fifth of the UK’s total GHG emissions in 2017. The majority (91%) of domestic transport GHG emissions come from road transport, with rail accounting for just 2%. Although UK net domestic GHG emissions fell by 32% between 1990 and 2017, GHG emissions from road transport increased by 6%. However, this is lower than the 28% increase in road traffic miles over the same time period, most likely due to improvements in newer vehicles’ fuel efficiency and emissions.

# Air Quality

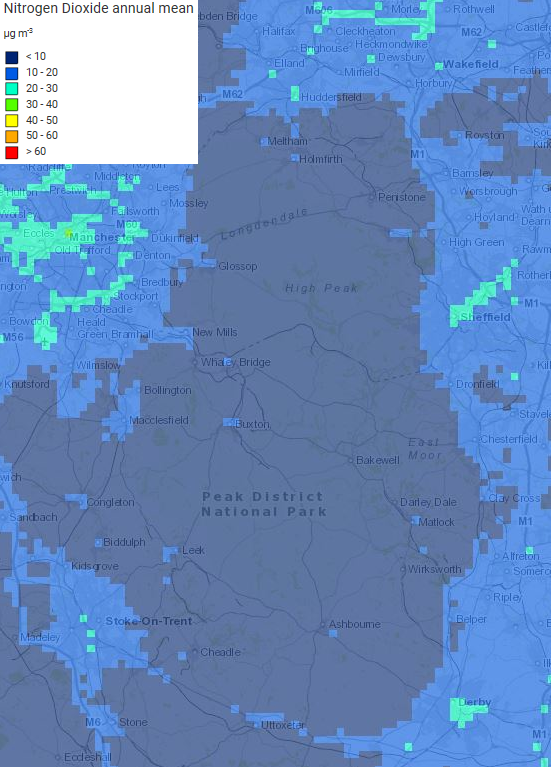

Clean air is a key feature of the Peak District National Park’s special qualities and particularly valuable given the heavily populated urban areas surrounding the area (see map below).

Peak District National Park and Surrounding Areas’ Annual Mean Nitrogen Dioxide Background Levels 2018.

Road traffic negatively impacts air quality through exhaust emissions as well as non-GHG emissions such as particulate matter and nitrous oxides. For instance, all vehicles, including electric vehicles, emit particulate matter from tyres, brakes and road abrasion. Particulate matter emissions from tyre and brake wear and road abrasion increased by around 25% between 1990 and 2017. Although overall non-GHG emissions from domestic road transport fell between 1990 and 2017, they are associated with negative health outcomes even at significantly reduced levels.

Diesel exhaust emissions and particulate matter from national rail travel also increased between 1990 and 2017, although this is unlikely to contribute significantly to air pollution within the PDNP due to the limited number of lines and stations within the boundary.

There is one Air Quality Management Area within the PDNP on the A628 at Tintwistle, which was declared in October 2018 due to a continued exceedance of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels. An Air Quality Action Plan to improve air quality is being developed by High Peak Borough Council and a number of measures have been taken. Area levels of NO2 have subsequently dropped from 49.9 microgram cubic meters at the time of declaration to 45.6 in September 2019.

# Environmental Factors Affecting Transport

Weather can impact the availability of transport and the ease of travelling to, from and across the Peak District National Park. Exposed and elevated transport networks and roads, such as the A628 Woodhead Pass or the A57 Snake Pass, are susceptible to the impacts of weather extremes, such as high winds, floods, snow and ice. Such weather combined with the natural topography and geography of the PDNP can lead to closure of road and rail networks.

Extreme weather events linked to climate change are likely to increase in frequency and severity. Nationally, extended periods of winter rainfall are estimated to be 7 times more likely in the future and summer heatwaves 30 times more likely, with extreme heatwaves expected to occur every other year by 2050. The PDNP’s road and rail routes are therefore likely to face increased obstructions as a result of the incremental impacts of hotter, drier summers and wetter winters combined with the impacts of extreme weather events such as flooding, heatwaves, landslips and severe snow and ice.

Similarly, opportunities for active travel to, from and within the PDNP can also be impacted by the weather and climate. Access to public footpaths, multi-user trails and open access land can all be restricted by weather events such as flash flooding, snow and ice, heatwaves and the risk of wildfires, as well as the long-term impacts of weather and temperature extremes, such as vegetation growth, waterlogging, erosion and the formation of potholes.

# Future Sustainability of Motor Vehicles

Existing modes of travel and current transport networks should become more sustainable in the future with improved engine and battery technologies and cleaner fuel sources. However, other less familiar or predictable technological advances are also anticipated to occur, such as autonomous and semi-autonomous vehicles or drone deliveries. While much of this is currently unknown, it is likely to have significant impacts for sustainable travel and transport within the Peak District National Park.

Electric vehicles (EVs) have the potential to positively impact sustainable travel and transport within the PDNP, helping to reduce some of the negative impacts of road traffic on aspects of the PDNP’s special qualities like clean air. EVs produce significantly fewer emissions than conventional petrol or diesel cars, particularly as the UK now gets more than half of its electricity from low-carbon and renewable sources. However, unless the overall volume of traffic reduces, road traffic will still negatively impact these aspects of the special qualities.

At present, the majority of cars in the UK are still petrol or diesel: at the end of 2018, just 0.5% of licensed vehicles in the UK were ultra-low emission vehicles (ULEVs), which includes electric vehicles, electric range-extender vehicles and plug-in hybrids. ULEV sales are already rising, with ULEVs making up 2.2% of all newly registered cars in 2018 – an increase of 20% in just one year. Future projections suggest UK EVs could rise to 36 million by 2040. 2018 also saw the first decrease in the proportion of newly registered diesel vehicles for 20 years, although newly registered petrol vehicles continued to increase.

Between 2015 and 2019, the number of UK public charging devices increased by 312% and continues to rise consistently. Despite this, as of May 2020, there were only 13 publicly available EV charging point locations within the Peak District National Park. This doesn’t prevent the use of EVs in the PDNP, however, as residents can charge EVs at home and visitors can use clusters of EV charging points around the PDNP. Although EV charging point provision in the PDNP might improve in the future, there are still significant issues preventing their roll out such as national grid energy supply and capacity and mobile signal coverage for payments.

There is also a trend towards electric bikes (e-bikes). Improved battery and motor technology means that e-bikes can now travel further and faster and are increasingly affordable. Their use is anticipated to expand significantly across the PDNP. Nationally, sales are increasing each year, with 70,000 sold in the UK during 2018 and anticipated sales growth of 30% during 2020.

# External Developments Affecting Transport

Road travel and levels of traffic within the Peak District National Park are affected by road improvements and changes outside the National Park, such as population growth, new housing and development. Such developments can make the PDNP more accessible and cross-Park transport routes more popular. This can increase overall traffic flows within the National Park and increase the numbers and size of freight traffic.

The pressure that the desire for connectivity between populated areas puts on the National Park’s transport network and infrastructure is compounded by the topography of some of these routes. For instance, the cross-Park A628 between Flouch and Tintwistle has limited capacity to meet increasing demand and is often subject to weather related incidents that result in road closures.

# Access to Services

Direct information on access to services within the Peak District National Park is not currently available. However, DfT data indicates that people living rurally have poorer access to key services overall. Nationally, over half (51%) of the rural population live in areas with the poorest accessibility to services, compared with just 2% of the urban population.

Those living in rural areas like the PDNP have double the average minimum travelling time to access key services by public transport and walking (30 minutes vs 15) as well as cycling (26 minutes vs 13) when compared to urban areas. Car use increases the average number of key services available rurally by 150% within 15 minutes and by 67% within 30 minutes when compared to public transport. However, even by car, average minimum travelling times to access all key services in rural areas are more than double those in urban areas.

According to the 2018 National Travel Survey, the majority (62%) of all trips nationally are taken by car. This figure increases for those living in rural towns (69%) and rural villages and hamlets (76%) like the PDNP. Additionally, people living in rural villages and hamlets travelled 47% further than the national average in 2017/18 across all modes of transport combined. This was primarily due to travelling a greatly increased number of miles by car.

People living rurally travel 43% further than average for all purposes and significantly further for commuting, personal business and shopping. The average distance travelled for shopping per year by people living in rural villages and hamlets is almost double (1,349 miles) the national average (741 miles). In terms of time spent travelling, residents in rural areas like the Peak District National Park tend to take fewer trips overall and spend less time travelling for commuting and education than the national average, but take significantly more trips of a longer duration for business, shopping, holidays and day trips, and sport and entertainment.

Rural communities often have older populations who experience worse health outcomes and have a greater need to access health and care services, but tend be restricted by remoteness and isolation, increased travelling costs and poor public transport provision. Rurally, the minimum travel time to a hospital is double that for urban areas, while 43% of the rural population cannot access their nearest hospital within an hour’s travel, compared with just 6% of the urban population. Even by car, people living in rural areas have on average two GP surgeries available within a 15 minute drive, compared to eight available in urban areas.

What are the gaps in our research & data?

Impact of Covid-19 on travel patterns and access to services: Seek feedback from parish clerks or carry out a resident’s survey to assess behaviour changes and establish whether any changes are likely to continue into the future.

Visitor experience during Covid-19: Carry out research to answer key questions such as: 1) Is recent busyness at certain locations and times likely to continue into the future and can this be influenced? 2) Was visitor experience in the PDNP during Covid-19 positive, particularly for new visitors? Will new visitors return? 3) Would visitors accept dispersal from hot spots?

Accurate data on electric vehicle charging points: Collect data to understand the distribution of EV charging points.

Barriers to electric vehicle use: Carry out research to understand resident and visitor views on EVs and what barriers prevent their use.

Particulate matter monitoring data: Expand monitors installed by Hope Valley Climate Action in the Hope Valley to include locations like Bakewell, Baslow and Stoney Middleton.

Climate change effects on the road network: Carry out research to gain a clearer understanding of the effects of climate change and severe weather events on the road network.