Vital benefits for millions of people that flow beyond the landscape boundary

# Natural capital & ecosystem services

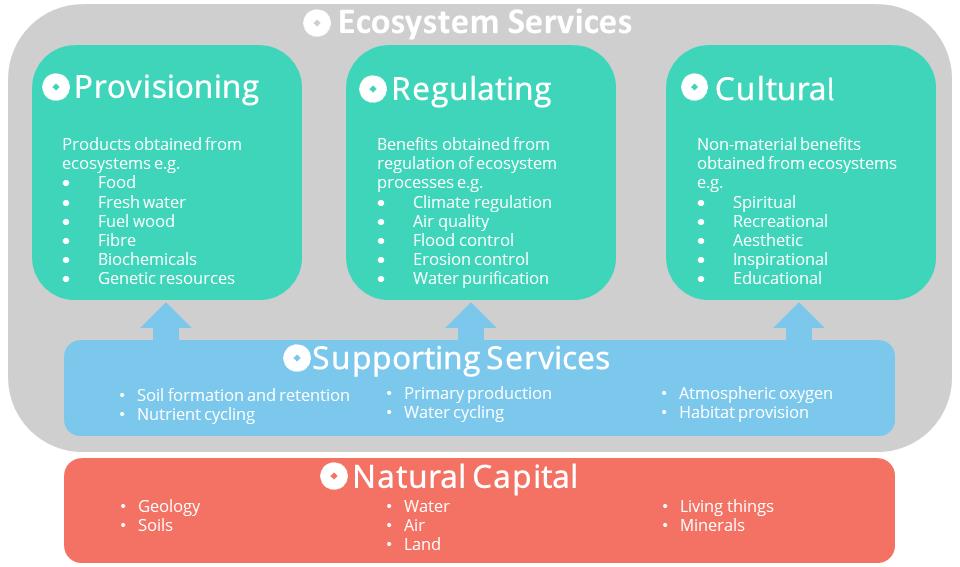

# Natural capital

Natural capital is our stock of waters, land, air, species, minerals and oceans. This stock underpins our economy by producing value for people, both directly and indirectly.

The term natural capital is increasingly used to describe the parts of the natural environment that produce value to people. Natural capital underpins all other types of capital – manufactured, human and social – and is the foundation on which our economy, society and prosperity is built [1].

Natural capital is commonly divided into renewable resources (agricultural crops, vegetation, wildlife) and non-renewable resources (fossil fuels and mineral deposits) [2].

It is from this natural capital that humans derive a wide range of services, often called ecosystem services, which make human life possible.

# Ecosystem services

There are four broad categories of ecosystem services [3]:

Provisioning services are products obtained from ecosystems such as food, fibre and fuel and genetic resources

Regulating services are benefits obtained from the regulation of ecosystem processes and include maintenance of air quality, climate regulation, water regulation and purification, erosion control, natural hazard protection and removal of pollutants

Cultural services are non-material benefits that people obtain through spiritual enrichment, cognitive development, recreation and art

Supporting services are necessary for the production of all other ecosystem services and include soil formation and retention, nutrient cycling, primary production, water cycling, production of atmospheric oxygen and provision of habitats.

# Ecosystem services and the Peak District National Park

The Peak District National Park has a direct impact on the quality of life of those living within and outside its boundary. Its natural environment provides people with many important benefits, such as clean air and water, food, fuel and raw materials. Through its landscapes, the National Park helps to regulate our climate, store flood waters and filter pollution. It also provides opportunities for people to improve their health and wellbeing and enjoy cultural experiences. These benefits are often referred to as ecosystem services.

The impact of these ecosystem services is far reaching. At a local level, the condition of the air, water and soil of the Peak District is key to the quality of life enjoyed not only by those living in and around the National Park, but also by those visiting or working in it. The National Park also delivers a wide range of benefits to the surrounding regions, such as flood prevention and the provision of water. At a global scale, well-functioning ecosystems in the Peak District can help mitigate one of the biggest challenges to our planet: climate change.

The following data shows a selection of the ecosystem services provided by the Peak District National Parks. The data is split into National Character Areas and is taken from the National Character Area profiles [4]. It will be updated when future information becomes available.

Diagram of ecosystem services & natural capital

# Food provision

White Peak

The main agricultural products from the area are dairy products and meat (beef, lamb and pork). There have been recent increases in the average size of dairy farms. Although some of the land on the plateau has productive soils and a long history of cultivation, 85% of soils are Grade 4 or 5 (poor or very poor quality agricultural land). There is now very little arable production and few mixed farms.

The White Peak is an important area for livestock grazing. It contributes to the local economy, employment and helps to maintain landscape and habitats. The deep, rich loam soils, over 1 m thick in places, were deposited by strong winds at the end of the last ice age. They provide unusually productive agricultural land for 300 m+ altitude.

Dark Peak

This is an important area for rearing livestock. Soils are poor and there is little opportunity for arable crops due to climate, topography, altitude and steep slopes. 95% of the land is Agricultural Grade 4 or 5 (poor or very poor quality agricultural land).

Livestock production is the dominant agricultural system in this NCA and has a strong association with the area’s cultural services. In many locations, well managed livestock production systems have the potential to increase the overall food provision of this NCA while benefiting many of the other key ecosystem services. However, inappropriate stocking regimes (such as too many/few livestock at periods within the grazing calendar), with insufficient management and husbandry may have a significant detrimental effect on many key environmental services including biodiversity, soil erosion, water quality and climate regulation.

South West Peak

This is an important area for livestock farming, contributing to employment, economy and maintenance of important habitats. 97% of the commercial agricultural land is permanent grass or uncultivated land. 93% of farmland is grades 4 and 5 (poor), and there is little opportunity for arable crops due to climate, topography, altitude and steep slopes. In 2009, there were 30,400 cattle (beef and dairy), 138,200 sheep and 6,500 pigs. Between 2000 and 2009, livestock numbers declined: sheep by 16%, cattle by 15% and pigs by a third.

Livestock farming is the dominant agricultural system and with good animal husbandry, appropriate stocking levels, grazing regimes and sustainable increases in livestock there is the potential to increase the overall food provision of this NCA while safeguarding biodiversity, soil erosion, water quality, water storage, carbon sequestration and climate regulation.

# Timber provision

White Peak

Existing broadleaved woodlands are small-scale or difficult to access, meaning that timber extraction is often not economically viable. There is limited history of active management for timber production, so few trees are suitable for timber production. There is also very little recent history of coppice management for small diameter timber production.

Woodland covers 4% of the NCA, 41% of which is ancient semi-natural woodland. The majority (91%) of woodland in the area is broadleaved woodland, predominantly ash. Much of it is located in the steep-sided dales and cloughs and protected by both UK and EU nature conservation designations (SAC and SSSI). Very little of the area’s woodland is actively managed. Most is unsuitable for timber production due to its importance for nature conservation and recreation, the poor quality, size and volume of timber, and the difficulty of accessing sites due to steep slopes, unstable surfaces, lack of vehicle tracks and direct access to public highways. In addition to this, timber traffic on already busy narrow roads could be problematic.

Dark Peak

Most broadleaved woodland within the NCA is on steep valley sides or in cloughs, which has contributed to the lack of management. With much of the land unsuitable for woodland (due to the extent of other important habitats) or used for livestock rearing and sporting interests, there are limited places for woodland creation. However, opportunities have been identified to restore plantation on ancient woodland sites (PAWS) and extend cover of native woodland in appropriate locations, and to continue or reinstate traditional forms of woodland management.

Though 10% of the NCA is covered by woodland, much of this is semi-natural on steep clough sides making it difficult to utilise. There are significant blocks of plantation woodland associated with water capture and storage in the adjacent reservoirs and these provide a source of timber.

South West Peak

Historically the area was part of medieval Royal and private hunting forests. Topography inhibits management of some woodland. With much of the land used for livestock rearing and sporting interests, places for woodland creation are limited to lower hillsides and cloughs.

3,247 ha of woodland cover in the NCA (8% of area): 1,096 ha of conifers (3%) and 1,944 ha of broadleaves (5%). Very little woodland on higher ground. Many broadleaved woodlands are small and limited to cloughs and steep sheltered valley heads. Small groups of sycamore, beech or oak are associated with farmsteads.

# Water availability

White Peak

Average annual rainfall over the area varies between 850–1,600 mm/year (1961–90). River flows are mostly groundwater-fed, originating from the large upland catchment to the north-west. Water is available for abstraction from the Manifold and Dove rivers during periods of high flows, and restricted volumes are also available from the Wye and Derwent rivers at periods of medium to high flows. Water is also available for abstraction from the Alstonefield management unit of the limestone aquifer, but not other units within the NCA.

Water abstracted from rivers in the NCA is used principally for general agriculture, spray irrigation, industrial use, power generation and public water supply. There are only a small number of licensed abstractions from the limestone aquifer, primarily for quarrying. There is a significant commercial bottled water enterprise in Buxton and thermal springs at Buxton and Matlock.

Dark Peak

This NCA is a valuable drinking water catchment area, and contains a large number of reservoirs, such as in the Longdendale and Derwent Valleys. These provide drinking water to adjacent NCAs and distant conurbations such as Manchester, Sheffield, Derby and Leicester. Many fast-flowing streams drain the moorland plateau and the headwaters of many rivers rise in the NCA, including the Derwent, Don, Noe, Goyt and Etherow. In addition, the large expanses of blanket bog present in the NCA store and slowly release large quantities of water. Currently the contribution this service makes can be reduced when vegetation is damaged or removed preventing the bog habitat functioning correctly.

South West Peak

This upland catchment provides the source of several major rivers (Bollin, Churnet, Dane, Dean, Dove, Goyt, Hamps and Manifold) which feed into the Mersey, Trent and Weaver catchments beyond the NCA to the north-west, south and east. The moorland above Buxton provides part of the catchment for drinking water for Buxton Mineral Water.

The presence of extensive semi-natural habitats allows for good overall water retention and increases opportunity for groundwater recharge. Although there are no major aquifers, the geology of the uplands makes the area suitable for reservoir construction to hold water from upland streams and rivers. This resource provides a public water supply. The Errwood and Fernilee reservoirs fed by the River Goyt provide drinking water for Stockport and its surrounding area. Lamaload reservoir, located in the west supplies Macclesfield, and Tittesworth reservoir located in the south provides for an increase in water demand in Leek, Stokeon-Trent and the surrounding area.

# Climate regulation

White Peak

Maintaining heathland cover, semi-natural grassland, woodland and wetlands is important in order to prevent release of stored carbon and improve capacity to sequester/store carbon and increase resilience to climate change impacts. The role of woodland in carbon sequestration and storage is limited due to low cover.

The mineral soils that cover the majority of the NCA (92%) typically have a relatively low carbon content (between 0-10%). The peaty surface soils (covering approximately 7% of the NCA) will have a higher carbon content and are likely to be associated with areas of heathland, purple moor grass and wetlands. The small areas of broadleaved woodland and unimproved grassland will also act as carbon stores.

Dark Peak

The vast expanses of deep peat soils within the NCA are very important because of their role in the storage of carbon and other greenhouse gases. Unfortunately these soils have been extensively damaged by atmospheric pollution and historical land use resulting in large areas of bare and actively eroding peat. This reduces the ability of habitats like blanket bog to store carbon.

Significant climate regulation is provided by the large expanses of deep peat associated with the blanket bog and upland heath (37,000 ha or 43% of the NCA) habitats which generally have a carbon content of 20-50% and provide particularly high levels of carbon storage. Other soils are also important for carbon storage, but these are much more limited in extent than peat and therefore are of lesser importance when considering climate regulation. The existing woodlands perform a role in the sequestration and storage of carbon, though this is however limited due to the relatively low woodland cover of 10%.

South West Peak

Peaty and humus-rich soils afford a significant carbon storage function and are a priority for conservation. These soils are associated with the area’s extensive blanket bog, heathland and purple moor grass habitats, and woodlands. Blanket bogs sequester carbon where there is a good active sphagnum moss layer, while damaged bogs release significant amounts of stored carbon. In some instances, poor management such as high grazing levels or inappropriate burning regimes and wildfires have affected these soils.

The mineral soils covering the central moorland block have a high carbon content of up to a half. The soils with an organic-rich and peaty surface cover just under half of the NCA. These soils include the peaty soils of the slowly permeable wet very acid upland soils with a peaty surface (just under a fifth of the NCA), very acid loamy upland soils with a wet peaty surface (just under a fifth); and blanket bog peat soils (just under a tenth). Carbon storage is also provided by woodland (3,247 ha) and its underlying humus-rich soils.

# Regulating water quality

White Peak

Groundwater and surface water are closely linked due to the many fissures and underground passages in the limestone. This makes groundwater particularly vulnerable to pollution by anything applied to or spilt on the land. For example nitrate concentrations in groundwater more than doubled between 1967/68 and 2005 and in the Castleton area presence of faecal bacteria in cave water has been a problem in the past.

The rivers Wye and Dove are of ‘good’ ecological status, whereas the River Manifold, between Hopedale and Ilam, is of ‘poor’ ecological status (poor for diatoms and moderate for fish). The chemical quality of the River Dove is ‘good’. The chemical quality of the River Wye within the NCA has only been assessed between Buxton and Miller’s Dale, where it is good, and the River Manifold has not been assessed.

Dark Peak

The generally steep nature of the upland streams and watercourses running off the plateau, combined with significant areas of degraded habitats result in high levels of run-off, especially after heavy rainfall. High rainfall and bare peat both help to increase rates of erosion which result in increased sediment loading and discolouration of the downstream rivers. Blanket bog peat helps regulate water quality. Blanket bog vegetation helps prevent oxidation of bare peat which in turn causes the peat to be liable to erosion affecting water quality in rivers and causing discolouration of water.

The majority of rivers in the NCA have been assessed as either ‘moderate’ or ‘poor’ ecological quality, though some have also been assessed as ‘good’. Many rivers suffer significantly from artificial modification which is one of the main reasons for the moderate or poor designations (under Water Framework Directive requirements). In addition, diffuse pollution from agricultural activities and other sources can impact the quality of the water.

South West Peak

The South West Peak is upland in nature, relatively extensively managed and has low population density. This, together with 140cm of rainfall (per annum) and steep watercourses, result in rapid run-off, with consequent erosion and increased sediment load impacting on rivers downstream especially after heavy rainfall events.

39,611 ha (93%) of the NCA is classified as a Nitrate Vulnerable Zone (NVZ). Water quality for the majority of the NCA is classed as very good to fair.

# Regulating water flow

White Peak Infiltration of rainwater is generally good because of the highly permeable nature of the underlying geology. Some of the watercourses are fast flowing and show a flashy response to rainfall, such as the Derwent which runs through steep-sided valleys and drains and upland catchments with impermeable geology. Others in wider valleys that drain the permeable limestone, such as the Wye and Dove, flow more gently and respond more slowly to rainfall.

The settlements of Buxton, Bakewell, Tideswell and Ashford in the Water are at risk of flooding from the River Wye. There is localised flooding from Dale Brook at Eyam and Stoney Middleton. There is a risk of fluvial flooding in Ashbourne (outside the NCA to the south in the Needwood and South Derbyshire Claylands NCA) from the River Dove.

Some of the rivers, such as the River Lathkill, suffer from limited or lack of flow in summer, exacerbated by abstraction and loss of water into soughs and other disused mining infrastructure.

Dark Peak Large areas of the moorland plateau currently suffer from degradation of functioning blanket bog which can result in rapid surface flow during periods of rainfall. As a result of this, the upland streams, which rise on the moorland edge, have a steep gradient and tend to be fast flowing, can show considerable variation in flow rates after heavy rain. This causes the River Derwent, and its upland tributaries, to respond quickly to rainfall events which can result in the rapid onset of flooding in downstream settlements. Impervious shales in the valley bottoms can also add to this problem preventing the percolation of water, which results in greater levels of overland flow.

South West Peak The area has some of the fastest rising rivers in the country, with rapid run-off which has implications for erosion and downstream flooding, which could be exacerbated by an increase in storm events arising from climate change.

Steep topography and high levels of rainfall means that the headwaters of the Churnet, Dane, Dean, Dove, Goyt, Hamps and Manifold drain quickly forming fast flowing rivers which can cause flash flood events and local erosion issues. Flood risk is not a major issue within this NCA; however peak flows have been known to cause significant damage in Wildboarclough.

# Regulating soil quality

White Peak There are 7 main soilscape types in the NCA:

- Freely draining slightly acid but base-rich soils (71% of NCA).

- Shallow lime-rich soils over chalk or limestone (8%).

- Slowly permeable seasonally wet acid loamy and clayey soils (8%).

- Very acid loamy upland soils with a wet peaty surface (5%).

- Slightly acid loamy and clayey soils with impeded drainage (3%).

- Slowly permeable seasonally wet slightly acid but base-rich loamy and clayey soils (2%).

- Slowly permeable wet very acid upland soils with a peaty surface (2%).

Dark Peak

The slowly permeable, wet, very acid upland soils and the blanket bog peat soils contain significant volumes of organic matter. This is retained where extensive grazing and sustainable burning regimes are in place. However, these soils are at risk of losing their organic matter through a combination of unsustainable management practices, climate change and soil erosion.

South West Peak There are 9 main soilscape types in this NCA:

- Slowly permeable seasonally wet acid loamy and clayey soils, covering just under a third of the NCA.

- Freely draining slightly acid loamy soils (just under a fifth).

- Slowly permeable wet very acid upland soils with a peaty surface (just under a fifth).

- Very acid loamy upland soils with a wet peaty surface (just above a tenth.

- Blanket bog peat soils (under a tenth).

- Slowly permeable seasonally wet slightly acid but base-rich loamy and clayey soils (less than a tenth).

- Slightly acid loamy and clayey soils with impeded drainage (less than a tenth).

- Freely draining very acid sandy and loamy soils (less than a tenth).

- Freely draining acid loamy soils over rock (less than a tenth).

# Sense of place/inspiration

The Peak District was the UK’s first National Park. It is a distinctive and often scenically dramatic landscape of European and national interest.

This very distinctive landscape has an exceptionally strong sense of place created by:

- The steep-sided limestone valleys and gorges (for example, Dovedale) with clear rivers and streams, and daleside woodlands.

- Prominent limestone cliffs and caves (for example, Thor’s Cave).

- The high limestone plateau with its productive pastures and flower-rich meadows, dew ponds and strong networks of field walls.

- Traditional villages (for example, Monyash) and Victorian Spa towns (such as Buxton and Matlock Bath) and grand mill buildings.

- Archaeology, particularly bronze-age burial sites, ridge and furrow and disused historic mines and quarries.

- Long distance, panoramic views from exposed upland moors and pasture.

- Iconic geology, habitats and landscapes such as The Roaches and Ramshaw Rocks, Shining Tor, Three Shire Heads, South Pennine Moors (part), Peak District Moors.

# Sense of history

White Peak The area has one World Heritage Site (part of Derwent Valley Mills WHS), five Registered Parks and Gardens, 292 Scheduled Monuments and 1,428 Listed Buildings. The area has a particularly strong sense of history, with a high concentration of Neolithic and bronze-age earthworks (for example, Arbor Low), numerous iconic structures from the industrial revolution (such as Litton Mill) and good preservation of traditional buildings, settlement pattern and field boundary networks (for example Chelmorton). Remains from early mineral extraction are also a prominent reminder of the area’s past, particularly in the form of lead rakes. The numerous dew ponds scattered across the plateau are a reminder of times when people and farming were more dependent on natural, rather than piped, water supplies.

Dark Peak There is an abundance of prehistoric settlement sites on the open moors and moorland fringe: enclosed and unenclosed farmsteads, ring cairns, bowl barrows, small, irregular medieval fields surrounded by stone walls, strip fields, mine remains and linking ancient routeways. On the moors, historic packhorse trails crossing moorland tops are still evident and form part of well-used trails, while on the moorland fringes strong patterns are created by the drystone walls that enclose the fields. Many buildings are constructed in characteristic local gritstone with slate roofs. There is evidence of local quarrying which contrasts with pre-industrial development such as older settlements and farmsteads on the moorland fringe. The large and well known water reservoirs contribute to a strong visible sense of history.

South West Peak A sense of history associated with the remains of Mesolithic and Neolithic settlements, field systems at Lismore Fields (south west of Buxton) and the many Bronze Age barrows visible around the margins of the valleys. The medieval dispersed settlement pattern is still distinctive in the uplands. While the remnants of coal mining, including spoil heaps and buildings (particularly around Flash and Goyt’s Moss), and surviving mill buildings along the rivers provide links with the area’s industrial past.

12% SPA and/or SAC, 13% designated SSSI, 2 registered parks and gardens, 59 scheduled monuments and 665 listed buildings, 30 Local Geological Sites. Iconic sites, and landscapes such as The Roaches and Ramshaw Rocks, Shining Tor, Three Shire Heads, isolated field barns and farmsteads. A network of historic routes including ancient track ways and former packhorse routes particularly over the moorlands. A range of designated and undesignated heritage assets that reflect human use of the NCA from the end of the last glaciation to the present.

# Tranquillity

White Peak Tranquillity is a significant feature of this NCA, with 76% classified as ‘undisturbed’, a figure that has remained relatively static over the past fifty years following only a very small decline from 79% in the 1960s. Only 1% is classed as urban.

Despite a slight reduction in tranquillity (3% 1960s-2007), the NCA is extremely important in providing a rural/tranquil escape to nearby urban populations. Its central location and ease of accessibility means that high levels of visitors can be a threat to tranquillity.

The main source of disturbance is associated with the urban settlements of Buxton and Bakewell and the urban fringes of Matlock and Wirksworth. In addition, the main road corridors (A623, A6 and parts of the A515) all contribute to decreased levels of tranquillity in the north of the NCA.

Dark Peak The area is an important resource for tranquillity with 63% of the area classified as ‘undisturbed’ according to the CRPE Intrusion Map 2007 – though this is a decrease from 86% in 1960. The NCA is an especially important resource in terms of tranquillity and provides an area of escape for many people including those from the surrounding heavily populated urban areas including Huddersfield, Manchester, Chesterfield and Sheffield.

Despite the reduction in tranquil areas, this NCA is extremely important in providing experiences of wild open spaces for the many people living in the adjacent conurbations. Although recent development has occurred in the valleys, there remain many quiet and secluded areas within the NCA.

South West Peak This NCA is extremely important in providing experience of wild open spaces (with few structures or man-made roads) for the many people living in the adjacent urban areas. A sense of tranquillity is still strongly associated with the smaller, quieter river valleys (such as the River Goyt and Fernilee Reservoir) and the core of high open moorland.

High levels of tranquillity throughout the central upland moorland core away from settlements and road corridors, with 68% classed as ‘undisturbed’, although this has declined (by 10%) since the 1960s.

# Recreation

White Peak The NCA offers a network of rights of way totalling 1,080 km at a density of just over 2 km per km2 , including 51 km of the Pennine Bridleway, as well as 2,632 ha or 5% of the NCA which is publicly accessible. It also has good tourist and recreational facilities and a wealth of natural features that can be accessed for diverse activities including hill walking, rock climbing, caving and fly fishing.

The White Peak, along with the rest of the Peak District, is immensely important in terms of recreation for the Midlands, Yorkshire and north-west England. Its central location is easily accessed by adjacent urban populations mainly by road (car and bus), less so by rail.

Dark Peak The NCA offers a network of rights of way totalling 1,311 km, at a density of 1.5 km per km2 as well as a significant area of open access land covering 46,180 ha or 53% of the NCA. Further opportunities for recreation are provided by the Pennine Bridleway and Pennine Way. In addition to this, the whole area is a major draw for recreation and tourism with the Peak District National Park accounting for 84% of the NCA.

South West Peak The NCA offers a network of rights of way totalling 1,023 km at a density of 2.4 km per km2, as well as a significant amount of open access land covering 7,164 ha or 17% of the NCA.

Other recreation opportunities include CROW access land (7,234 ha), Country Parks (608 ha), Woods for People (406 ha), Common Land (29 ha), Local Nature Reserves (13 ha), National Trust, Forestry Commission and National Park owned sites; reservoir sites for example Tittesworth, Macclesfield Canal. Distinctive geology of ridges and tors such as The Roaches, Ramshaw Rocks and Shining Tor, as well as Three Shire Heads, South Pennine Moors (part), Peak District Moors.

# Biodiversity

White Peak Over 20% of the NCA is covered by priority habitats, with nearly 10% of the NCA protected by national and/or European nature conservation designations (SSSI, NNR, SAC or SPA). 68.2% of the White Peak’s SSSI are in favourable condition, and 27.3% are unfavourable recovering.

Much of the wildlife value and biodiversity is concentrated in the steep-sided limestone dales and gorges, which have been protected from development and agricultural improvement by their relative inaccessibility. They contain clear rivers and streams, species-rich flushes, semi-natural ash woodlands, scrub and flower-rich limestone grasslands. Many priority species are associated with these habitats such as white-clawed crayfish, bullhead, lamprey, trout, dipper, water vole, Jacob’s ladder, small leaved lime and white hair streak butterfly.

The rivers support abundant plant life (including water crowfoot and watercress), and have an important impact on the wider ecology of the dales as they support swarms of hoverflies, mayflies and dragonflies, which in turn support important populations of birds to the dale-side woodland and scrub. The rivers flowing below ground through the cave network also support a wealth of wildlife including fish, eels, leeches and shrimps. The adjacent limestone cliffs and crags are also important for birds such as ravens and peregrines. Cave systems are important for bats.

The limestone plateau is significant for its historic dew ponds (with great crested newts), traditional hay meadows and its mosaic of open grassland habitats for ground nesting birds. Calaminarian grassland is an important and rare habitat that has developed in association with the remains of lead mines, and supports rare plants such as spring sandwort.

Dark Peak SAC and SPA European designations currently cover approximately 49,406 ha or 57% of the NCA while 40,443 ha (47%) has been designated as SSSI. 55% of the NCA or approximately 47,600 ha is currently recorded as being a priority habitat. Much of the nationally and internationally designated areas still suffer from historic atmospheric pollution and previous unsustainable management practices.

South West Peak There is over 11,703 ha (41% of the NCA area) of BAP priority habitats within the NCA, including key ones of 2,958 ha of blanket bog, 2,186 ha of lowland dry acid grassland, 2,179 ha of upland heathland, 1,998 ha of purple moor grass and rush pasture, 988 ha of broadleaved mixed and yew woodland, and a number of other habitats. The NCA contains one SPA and one SAC, and 5,553 ha (just over 13% of the NCA) is nationally designated as SSSI and a further 9% Local Sites. These upland habitats include blanket bog and dry heath with species including cotton grasses, heather, bilberry, and crowberry.

15% of SSSI are in favourable condition, 75% unfavourable recovering, 5% unfavourable no change and 5% unfavourable declining. The habitats support significant communities of golden plover, red grouse, curlew, merlin and short eared owl. Rocky outcrops support important species of mosses, lichens and ferns; raven, small numbers of ring ouzel, with wheatear and whinchat on the slopes below. On the in-bye land where it is heavily grazed the acid grasslands support curlew, snipe and skylark. Woodlands support breeding redstart, tree pipit, wood warbler, lesser spotted woodpecker and pied flycatcher.

# Geodiversity

White Peak This area has many outstanding karst features (including caves, sinkholes, outcrops, cliffs, gorges and tufa), recognised by a particularly high concentration of 18 geological and 10 mixed interest SSSI and 97 Local Geological Sites. The predominant geology is Carboniferous Limestone, with veins of minerals such as fluorspar, galena, chalcopyrite, barite and Blue John. There are also three types of igneous rock: dolerites, basalts and tuffs. Many of the features and sites are within the National Park and some are easily accessible and well used by schools, universities and specialist groups for recreation and education.

The geology and minerals of the area are still economically important. Limestone is still actively quarried as are fluorspar and Blue John. These provide jobs and income for the area, but can also have negative impacts on the local environment, landscape and tranquillity. The limestone of the area has long been important for construction of buildings, structures and walls, meaning that the geology is highly visible in the landscape.

Dark Peak There are currently 8 nationally designated geological sites within the NCA and a further 5 mixed interest SSSI. 75 local sites of geological interest have been designated within the NCA.

Features and designated sites within the NCA (many of which are in the National Park) are exceptionally well used (including by schools and universities) and are very accessible allowing for interpretation, understanding and continued research into the geodiversity of the NCA. Exposure of these features also makes a positive contribution toward sense of place and sense of history.

South West Peak 2 mixed interest SSSI designated for associations with historic mineral extraction. 30 Local Geological Sites Exposed rocky tors and boulder slopes. Local building tradition demonstrated through use of local materials including gritstone for walls and stone slates.

The distinctive Roaches, Ramshaw Rocks and Windgather Rocks are popular sites for climbing and walking. Geological sites and distinctive topography provide accessible exposures allowing for interpretation, understanding and continued research into the geodiversity of the area. They also contribute to sense of place and history.

Disused quarries previously supplying a source of local building materials demonstrate the robust architecture and visual cohesion in the landscape. Edges, tors, quarries provide important habitats for wildlife. Coal mining area – now abandoned but remains evident – past exploitation links geology and history of land use.

What are the gaps in our research & data?

- Ecosystem services cover a broad range of information, not all of which is available, readily updated or easy to analyse.

- The ecosystem services information in the NCA documents is out of date and this data needs updating.

Natural Capital Committee: https://www.naturalcapitalcommittee.org/natural-capital.html ↩︎

Business Directory: http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/natural-capital.html ↩︎

GOV.UK: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/69192/pb12852-eco-valuing-071205.pdf ↩︎

GOV.UK: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-character-area-profiles-data-for-local-decision-making/national-character-area-profiles ↩︎