Landscapes that tell a story of thousands of years of people, farming and industry

# Cultural Landscapes

Alongside our most significant designated heritage sites, there is a wealth of non-designated heritage assets across the region. These include stone circles, barrows, field systems, lead mines, quarries and mills, and much more. Taken together, our heritage assets are an important reminder that all our landscapes are culturally produced, and the influence of humans stretches back tens of thousands of years.

The vast majority (95%) of cultural heritage ./img within the PDNP are not covered by any formal protection, but they still contribute greatly to the character of our places and landscapes, to our sense of place, and to our own understanding of how humans have shaped the world. A historic site or heritage asset may have significance in its own right, but it usually more meaningful to look beyond the individual site, and consider the wider landscape context.

Some important themes and historic features that underpin the Peak District landscapes are summarised below.

# Places to Live in the Landscape

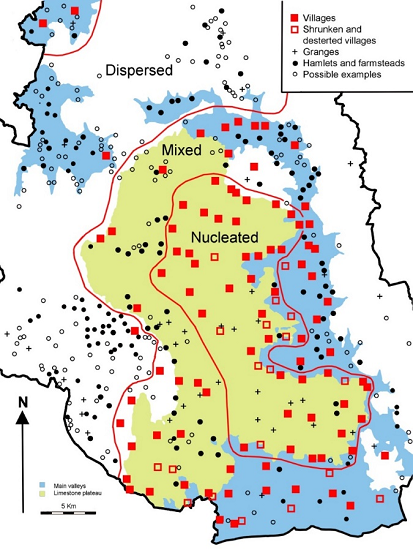

This is a relatively densely inhabited National Park and settlements are a vital part of landscape character. The distinctive vernacular tradition is a strongly defining feature of this upland region. The pattern of nucleated and dispersed settlement is also closely related to the underlying geology and topography.

Map showing Nucleated Villages in the White Peak and Limestone Plateau.

Many settlements have medieval origins (see map below), although much of the current building stock is of 18th and 19th century date, when many timber-framed buildings were rebuilt in stone; once-common thatched roofs are now extremely rare here. Our conservation areas celebrate the most important parts of these, and therefore we have a good survey and evaluation data relating to these settlements along with the listed buildings scattered throughout the National Park landscape (see the heritage assets protection section).

Map showing Nucleated Villages in the White Peak and Limestone Plateau.

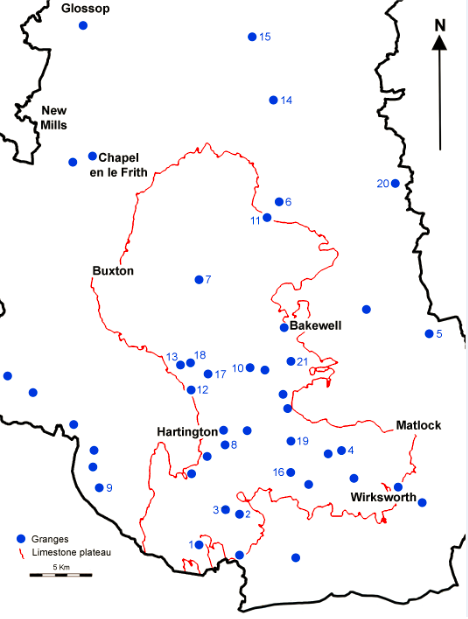

1. Musden 2. Newton 3. Hanson 4. Ivaonbrook 5. Harewood 6. Abney 7. Blackwell 8. Biggin 9. Onecote 10. One Ash 11. Grindlow 12. Pilsbury 13. Needham 14. Crookhill 15. Abbey 16. Roystone 17. Cotesfield 18. Cronkston 19. Mouldridge 20. Strawberry Lee 21. Meadow Place

# Extensive Urban Surveys

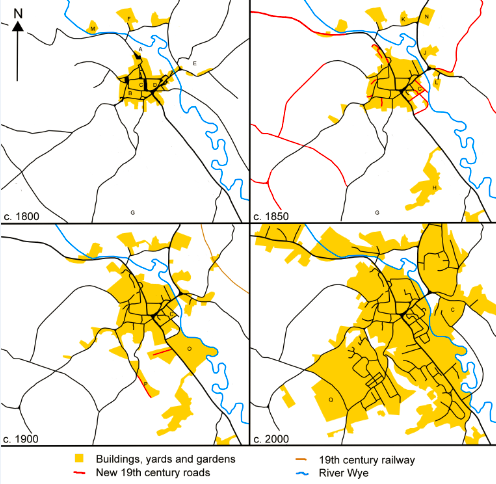

The PDNPA Historic Environment Record and Parish files show information about the places and landscapes of the National Park. It contains ‘urban’ survey reports for four of our settlements; Winster, Bakewell, Tideswell and Castleton. These are detailed desk-based assessments summarising the history of development and the known and potential archaeological resource of the settlements as can be seen in figure 10. This level of mapping is not available for every medieval settlement but further information can be found on the Historic England Website [1].

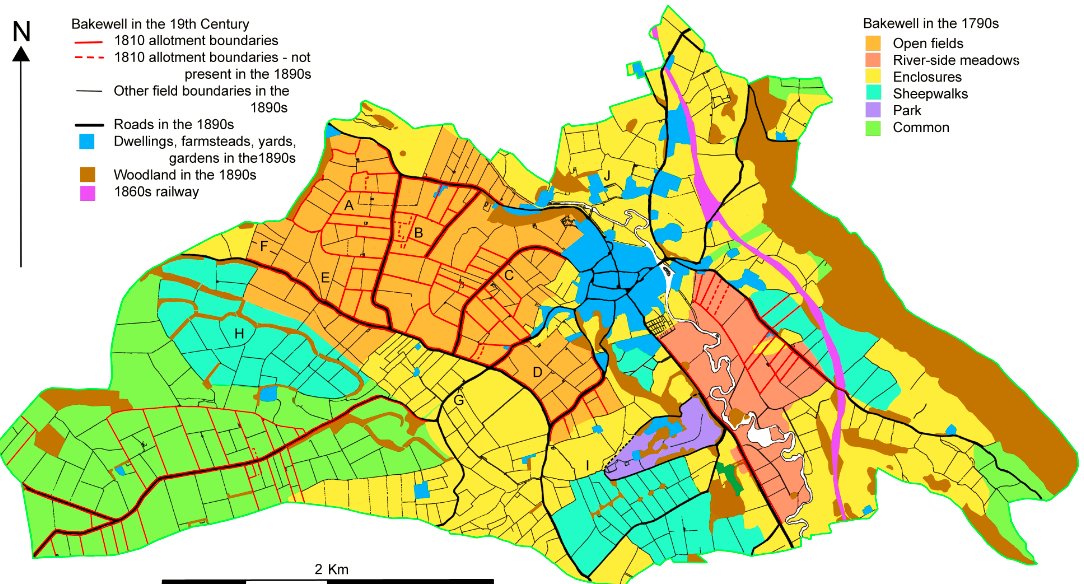

The Development through Bakewell at 50 year intervals Historic Mapping 1796, 1799, 1852 & 1898.

# Farming and Fieldscapes

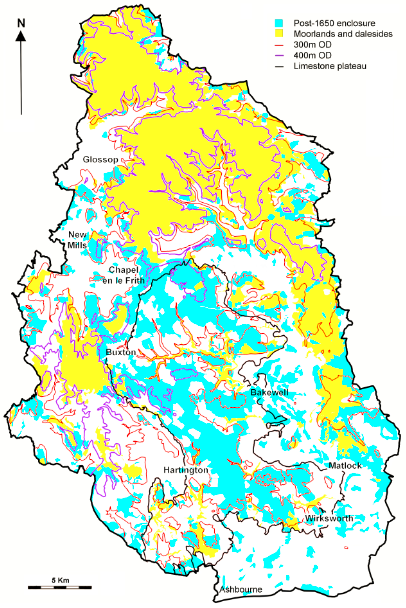

The historical development of our agricultural landscapes is a major contributor to our current landscape character areas. We have evidence for farming practices from the Neolithic period onwards; the placename ‘grange’ is common and attests to the relationship of a medieval farm to a monastic site, usually in the more agriculturally-productive lowlands. But it is our post-medieval agricultural practices, and enclosure in particular, that have probably had the greatest impact on how our landscapes look today. Our understanding of farmsteads, barns and outfarms, and threats to their survival, has been greatly enhanced by a recent mapping research project.

Landscape view showing well-preserved fossilised open fields defined as drystone walls Litton. The land in the middle distance was once open common land until enclosed in 1764 [John Barnatt].

Many areas of the Dark Peak and uplands remained open land. Research (the nap below) shows the spatial relationship between enclosure in the PDNP and altitude.

Post 1650 enclosure and today’s moorland and dalesides.

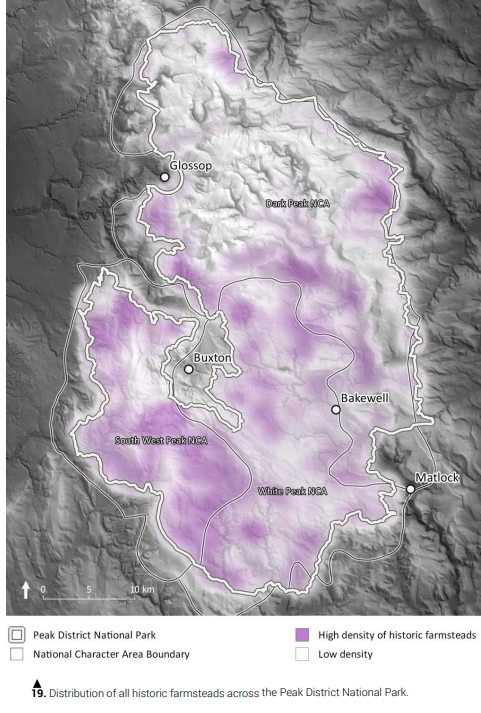

# Farmsteads Mapping in the Derbyshire Peak

The PDNP has amongst the highest levels of survival of traditional farmsteads, comparable to other upland areas and above average for other parts of England that have been mapped. The (2015) Farmsteads & Landscape project mapped 2523 farmsteads, 2614 outbarns and field barns. Almost 90% of farmsteads in PDNP have heritage potential due to the retention of some or all of their historic form. Some are in disuse, derelict or converted to alternative uses, but the overall picture is very positive when compared nationally.

Across mapped areas of PDNP, over 83% of farmsteads survive with more than 50% of their historic form intact, a very high percentage in a national context. 73% of dispersed cluster plans retain more than 50% of their historic form, whilst 83% of loose courtyard plans with buildings to one or two side of the yard retain more than 50% of their historic form. This is better share of retention than other areas of lowland England that have been mapped.

At National Character Area level, the White Peak has the highest levels of survival (87%) and the lowest % of farmsteads completely lost from the landscape since c1900 (3%). In the SWP, 83% of farmsteads have survived, while the Dark Peak has 79% of farmsteads surviving, and a higher level of complete loss of farmsteads (11%). A second phase of the project resulted in the Farmsteads Character Statement and Farmsteads Assessment Framework. Taken together, these resources help us to understand the different influences within each national character area and help us to manage change.

Distribution of all historic farmsteads across the Peak District National Park.

# Changes in field boundaries & agricultural landscape features

Agricultural practice in the PDNP has created a rich palimpsest of field boundaries amongst other agricultural features such as dew ponds or ridge and furrow (figure 16). These have been created for the most part over the last 600 years . Some field boundaries are medieval in origin, but most field patterns that exist today, date back to 250 to 150 years with ‘ruler-straight’ walls from when many of the regions commons were enclosed.

Bakewell in the 19th Century.

This maps shows this rapid change in enclosure of field boundary change for the Parish of Bakewell. Change happened later here (1810) than around many other of the PDNP hamlets and villages. The Historic Landscape Characterisation project covers the entirety of the National Park and traces the change in character from the mid 1600s onwards; each has its own story to tell.

The largest landscape-wide survey undertaken of modern field boundary change was the 1991 Countryside Commission report; Landscape Change in UK National Parks [2]. The report published the results of monitoring of landscape change in National Parks in England and Wales and compared aerial photography of each National Park from dates in the 1970s with the late 1980s. This enabled an assessment to be made of change in land cover, as well as linear and point landscape features. This showed during that period the Peak District lost 42km of hedges and 230km of walls. Overall trend of net loss or gain has not been measured since.

Further evidence of agricultural features are contained within the PDNPA aerial photography archive or those from Historic England such as image below. Oblique Photographs are particularly useful for understanding cultural landscapes and their settings whilst keeping a record of visual condition of the heritage feature over time. Features observed on aerial photographs are usually mapped into the HER.

Aerial Photography showing ridge and furrow and lynchets in the agricultural Landscape surrounding the village of Ballidon [Historic England Archive 7433_51].

# Monitoring cultural features at a large spatial scale

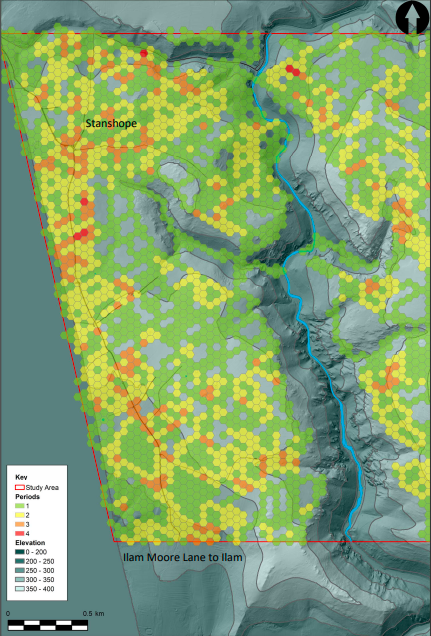

Lidar data, can help enrich the rapid assessment monitoring of heritage features in the agricultural landscape. Currently the PDNP Lidar data is available from the Environment Agency and coverage poor with only one third available for the PDNP. Recent research by a student at the University of Oxford [3] in the PDNP, has taken advantage of this data. The research explored visual representation of time-depth in multi-period landscapes derived from various aerial sources. The method analysed the period count and cumulative age, and translated this information into a more readily comprehensible visual representation. With the use of hexbin mapping (map below) it is possible to look for hotspots of cultural features at a landscape scale across the PDNP. This method is being further developed for a more in-depth PhD research project.

Topography of the study area overlain by hexagon tessellation, representing the time-depth based on the count of archaeological features in each polygon (data source - Environment Agency copyright and/or database right 2019).

No one single method of investigating historical landscapes is usually sufficient to cover all aspects of archaeological remains and reveal the archaeological features within them. And the scale at which these features are identified means that condition is difficult to ascertain without field survey. However, there is potential to extrapolate this method across the PDNP to understand trends of loss or gain at a landscape scale.

# Stones and Minerals

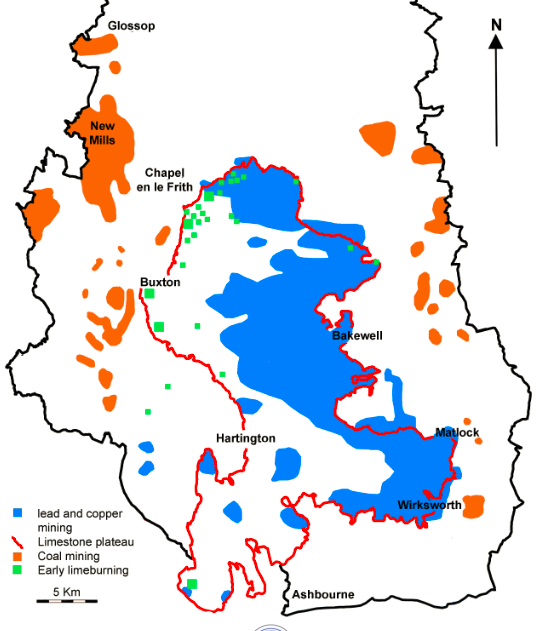

The exploitation of stone and mineral resources, especially limestone and gritstone, has shaped the Peak District landscape since prehistoric timesand continues to do so. Zinc, lead and copper ores are located on the limestone plateau, and coal, fireclays and ganister have been mined on the western and east gritstone uplands. Rare evidence for Bronze Age copper mining is found at Ecton, and the lead orefield is one of the most important in Britain, with extraction taking place from Roman times to the 20th century.

Distribution pf the main lead and copper mining locations in relation to the limestone plateau with coal mining beyond to the east & west.

# The Lead Legacy Project

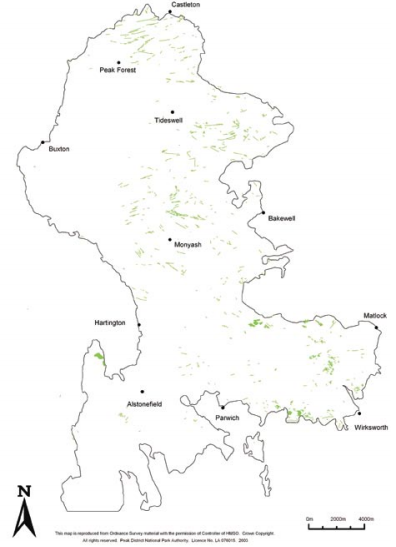

This project, undertaken by the PDNPA, mapped all the known extant and removed surface remains of historic leadworking. These are important habitats (e.g. supporting lead-loving plant species) as well as significant heritage ./img. About three-quarters of these important features have been removed or are in significantly damaged condition. Only a small percentage of identified high-priority examples are protected, some through statutory designation and others conserved short-term by agri-environment schemes.

Oxlow Rake, with Cop Rake to the left, are highly visible ancient mining sites crossing the landscape near Peak Forest (National Monuments Record/English Heritage).

The best preserved examples and areas were identified as High Priority Lead Working Sites and Landscapes and information is held in reports as well as in spatial datasets.

The distribution of lead mining remains in the Peak District Orefield which survive in reasonably good condition (green).

Although the best sites are now scheduled monuments, there is an ongoing threat to non-designated surface lead workings from infilling, usually relating to present-day agricultural use of the land.

# Routes through the Landscape

Roads, tracks and paths form a network across our landscape, and some will have prehistoric origins. Some are known to be Roman in date, while many are medieval or later. Significant routeways cross over some of the more remote moorland landscapes, and can in places be seen as deeply-worn ‘holloways’, often with several distinct strands or braids covering many tens of metres in width. Eighteenth-century stone guidestoops are sometimes found on remoter parts of older routes giving directions and distances to key market destinations.

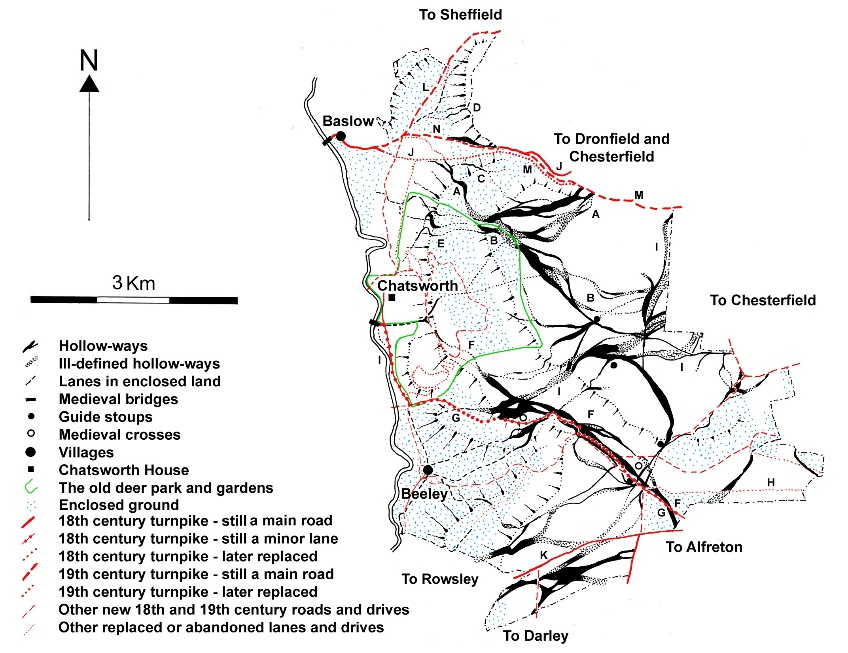

The PDNPA and partners have surveyed many of these historic routes and mapped them (see map below). Each of the sites that have been mapped have been done independently depending on the scope of the project. There is no spatial data set which lists every single historic route, either in use or abandoned. However, surveys like this one in Chatsworth (figure 13) help us to appreciate the complexity and extent of features in the Peak District landscape.

Traditional routeways roads and drives on the Chatsworth Estate East of the River.

# Using Water

Water has been harnessed to provide power for hundreds of years, traditionally for milling cereals, but later for industrial processes such as cloth manufacture and pigment grinding. Traces of water-powered industrial sites, both large and small, are scattered throughout the National Park. The creation of reservoirs for the supply of water to the surrounding towns and cities began in earnest in the 19th century and today some of the dam structures form some of the Park’s most well-known landscape views. The management of some of the water catchments has led to some areas of planned agricultural abandonment, such as around the Digley Reservoir near Holmbridge. The remains of buildings that were submerged for the creation of reservoirs still hold a fascination for many, and provide a significant focus for public interest in times of low water.

# Landscapes of Deeper Time

The National Park holds a wealth of ancient sites, and the prehistoric ceremonial monuments are probably some of the most well known. Arbor Low, with its series of recumbent stones set inside a large henge bank is unique and impressive but there are many more modest stone circles, often close to the moorland fringes. The concentration of Bronze Age settlement and fieldsystems on the lower gritstone shelves on the eastern side of the Park is of national significance. In many places, the deep time depth of the landscape can be appreciated because earthworks are preserved under pasture or in areas where agriculture has not been intensive. Relict fieldsystems from the Bronze Age to through to the medieval periods are found in numerous locations. The Bronze Age settlement and fieldsystem on Big Moor (a scheduled monument) cover an area of 208 hectares.

The density of Bronze Age barrows, often on prominent hilltop locations in the White Peak, is one of the highest in the country.

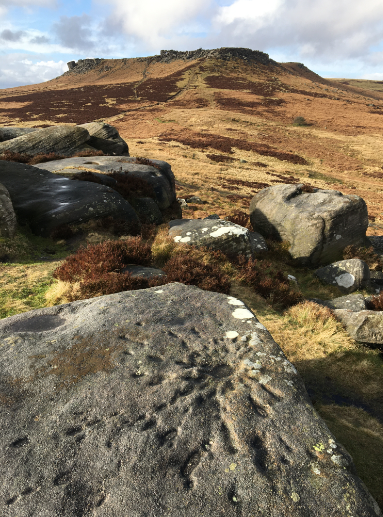

Intensive archaeological fieldwork investigations, such as those at Gardom’s Edge, remind us that areas that seem today seem relatively ‘wild’ were once places of settlement, agriculture and ceremony and provide us with important information about long-term landscape and climate change and adaptation.

# Medieval Elites

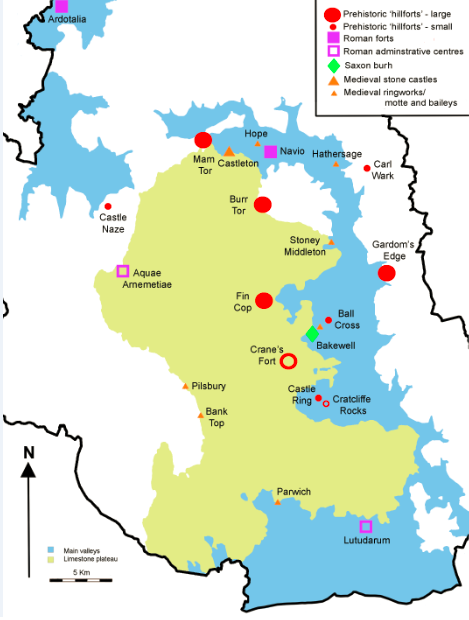

Several motte and bailey fortifications indicate the influence of ruling medieval elites; perhaps the best example can be found at Pilsbury. The only stone castle to be built in the Peak District is found on the steep slopes above Castleton, where the natural landform forms part of the dramatic castle defences.

Many of the Peak villages have medieval churches, although significant numbers were rebuilt or restored in the 19th century. Pre-Norman crosses, often just in fragments, are found at several church sites; Alstonefield and Bakewell have significant collections.

The distribution of prehistoric hillforts, Roman forts & other administrative centres, & medieval defended sites.

# Polite Landscapes

Lands of the crown, aristocracy and landed gentry have had a significant influence on parts of the Peak District landscape. There were both royal and private medieval hunting ‘forests’ in and around the Peak; the Royal Forest of the Peak covered much of north-west Derbyshire. From, the 16th century onwards, mansions and halls were established, and the fashion for formal gardens later developed into an application of more naturalistic landscapes and carefully created parkland, such as that seen around Chatsworth House and at Lyme Park in the 18th century – the epitome of the Picturesque.

These landscapes, and also the ‘sublime’ natural landforms such as Dove Dale, became tourist destinations in their own right. Many of the open moorlands are the result of careful land management by the larger estates for shooting pursuits, and lodges carriage drives and shooting butts are still present in these landscapes.

The larger estate parklands have been subject to extensive archaeological survey, but ever-improving availability of Lidar data will continue to provide opportunities for enhancing our understanding of parklands of all sizes.

# Conflict Landscapes

Traces of military activity, mostly relating to training, survive in several parts of the National Park, and particularly on its moorlands. On the eastern edge are nationally-significant WWI and WWII practice trenches and a barracks site, subsequently used in both World Wars as a POW camp. Another very rare WWII POW camp survives, in part, at Biggin. Off the Houndkirk Road are the remains of a WWII ‘Starfish’ bombing decoy site which was established to protect Sheffield.

Mortar scars, shallow pits (‘fox holes’) and bullet scars attest to assault training around Burbage Valley and on Ramsley Moor. More than a century of military training on Merryton Low has also left ephemeral traces, revealed when vegetation cover was destroyed in a moorland fire in 2018. Anchor bases of some reservoir defences are still in place on the eastern side of the Park.

Photograph Scheduled Monument Carl Walk - mortar scar on gritstone.

# Intangible Landscapes

Across the Peak District, intangible heritage includes customs and traditions, such as traditional crafts, skills and techniques vital to maintain the vernacular architecture and sense of place found across the contrasting gritstone and limestone landscapes. Fundamental to this is the concept of not only protecting physical remains, but focussing on safeguarding the transmission of traditional skills and knowledge.

The Peak District is also rich in arts and literature, including myths, legends and folklore. The right to roam and the social heritage of the Kinder Mass Trespass are as tightly integrated into the historic environment of the Peak District as Chatsworth House, or Peveril Castle. Many Parishes still undertake ‘well dressings’ in their local community [4].

An evaluation of the impacts of heritage funding found that 56% of local community members agreed that the site ‘provides me with an important connection to this area’s history’ [5]. An academic research study, found that the young participants especially experienced an enhanced sense of sense of identity, increased ‘social connectedness’, as well as a greater attachment to place. Amongst elderly participants, personal memories and recollections created the stronger link to aspects of identity [6]. However, these less tangible elements of the Peak District cultural heritage and historic environment are hard to identify, and even harder to measure and record.

What are the gaps in our research & data?

- Human landscapes: Understanding and continuing to research the extent of human influence on all of our landscapes is critical to managing change into the future.

- Intangible heritage: How do we record our less tangible heritage? How do we best ensure its long-term protection and ensure it is fully acknowledged in policy and decision-making?

- Landscape monitoring: It is imperative to monitor landscapes, as well as individual sites but this needs considerable resource – how can we best use remote techniques such as aerial photographs or drone surveys? What is happening to heritage ./img at a landscape scale? (e.g. lead rake infilling, impacts of climate change) and how do we respond appropriately?

- Climate change: what are the specific environmental and climate change factors impacting cultural heritage ./img and landscapes?

Historic England: https://historicengland.org.uk/research/current/heritage-science/Atlas-of-Rural-Settlement-in-England/ ↩︎

Natural England: http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/5216333889273856 ↩︎

Mapped in depth: A multi-period landscape explored visual representation of the time-depth mapped from lidar in the upland landscape of the Dovedale, Peak District National Park. Martina Tenzer ↩︎

PDNPA: https://www.peakdistrict.gov.uk/looking-after/living-and-working/your-community/village-plans ↩︎

Heritage Fund: https://www.heritagefund.org.uk/sites/default/files/media/research/impact_hlffunding_visitorsreport2009.pdf ↩︎

http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/117419/7/Action%20heritage%20research%20communities%20social%20justice.pdf ↩︎