Characteristic settlements with strong communities and traditions

# Local rural economy

The rural economy has strongly influenced the landscape, with over 87% of the Peak District being farmed. In turn, market towns and local businesses benefit from the National Park’s strong rural and visitor economies based around the Peak District landscape.

# Market towns

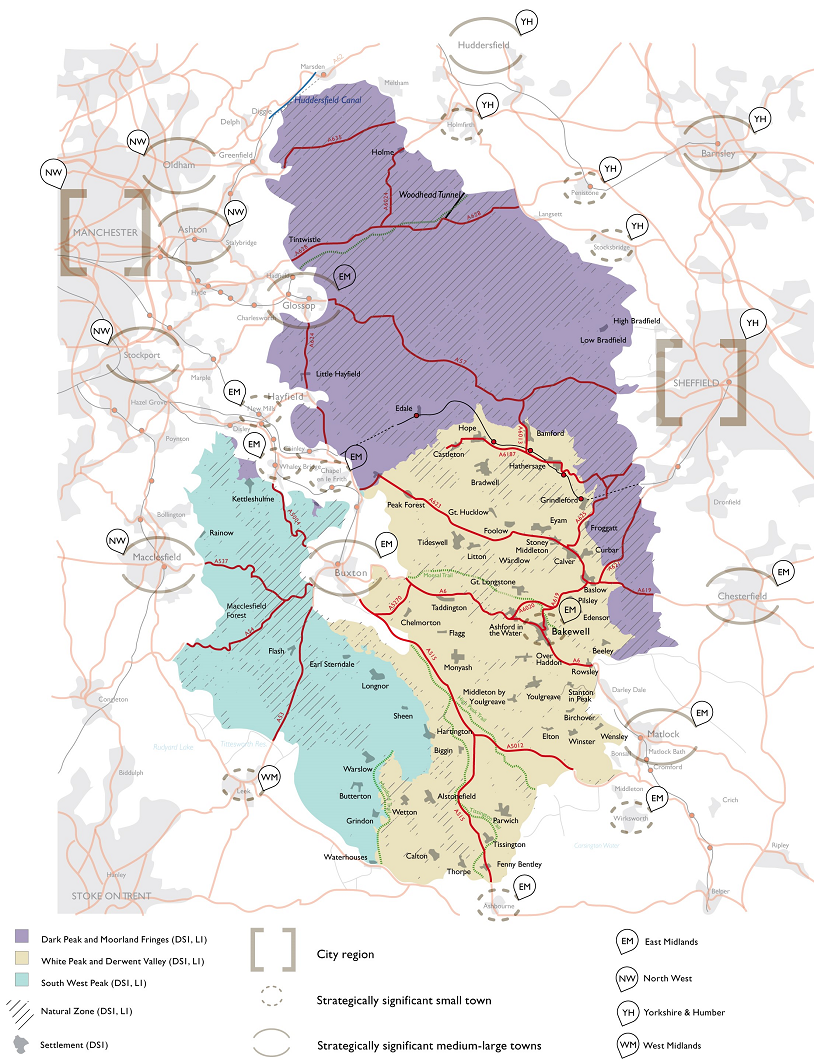

Market towns surrounding the Peak District boundary are strategically significant and serve a vital role for the rural economy (see map below)[1]. They act as focal points for business investment and economic development outside the National Park boundary, helping to reduce pressure within it. Market towns such as Matlock, Buxton, Glossop and Leek serve Peak District residents as well as benefiting visitors to the Peak District, acting as gateways into different areas of the National Park.

Market towns and businesses depend on the quality of the landscape and environment as well as the distinctive and characteristic settlements of the Peak District. Levels of both in and out-commuting are high for work and jobs. The market towns surrounding the National Park are reliant on the industries that drive the local visitor economy. In particular, the regional food and drink industry is largely supplied by, and associated with, the landscape and environment of the Peak District. This is one example of the complex interdependencies that the National Park economy has with neighbouring urban communities and market town economies.

Strategically significant settlements around the PDNP.

# Bakewell

Bakewell is the only market town within the Peak District (the only settlement with a population of more than 3,700), containing a larger range of services and retail and business opportunities than anywhere else in the National Park. It acts as a significant service hub for local residents as well as for many other rural and farming communities dispersed in the hinterland.

The town also serves as a significant visitor destination, being a popular location in its own right as well as a starting point for further exploration of the Peak District. Bakewell’s distinctive character as both agricultural market town and business centre highlights its unique role and importance to the economy of the area [1:1].

However, recent evidence from the Peak District Partnership [2] show market towns such as Bakewell (like many rural market towns) are facing many challenges, from changes in the demographics of local residents to the availability of broadband [3].

The latest data shows there are approximately 3,975 total employment jobs in Bakewell (table below). Updating analysis in the Bakewell Employment Land Review 2016 [4] shows there has been a growth in employment (from 3,500 in 2016).

The largest sector is now the arts, entertainment and recreation services, with 16% of all employment compared with 5% nationally. The retail and accommodation and food services sectors are now the second and third largest sectors, each forming a quarter (26%) of all jobs. They highlight the town’s prominent tourism-based economy.

Business Register and Employment Survey 2018: open access [Bakewell LSOA 002B, 003A & 003B]

| Broad Industrial Group | Bakewell: count | Bakewell: percent | GB: count | GB: percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 : Arts, entertainment, recreation & other services (R,S,T and U) | 620 | 16% | 1,397,000 | 5% |

| 9 : Accommodation and food services (I) | 560 | 14% | 2,318,000 | 8% |

| 7 : Retail (Part G) | 480 | 12% | 2,878,000 | 9% |

| 17 : Health (Q) | 450 | 11% | 3,960,000 | 13% |

| 3 : Manufacturing (C) | 375 | 9% | 2,435,000 | 8% |

| 16 : Education (P) | 290 | 7% | 2,626,000 | 9% |

| 13 : Professional, scientific and technical (M) | 250 | 6% | 2,685,000 | 9% |

| 10 : Information and communication (J) | 140 | 4% | 1,275,000 | 4% |

| 12 : Property (L) | 140 | 4% | 579,000 | 2% |

| 4 : Construction (F) | 135 | 3% | 1,494,000 | 5% |

| 14 : Business administration and support services (N) | 125 | 3% | 2,725,000 | 9% |

| 6 : Wholesale (Part G) | 80 | 2% | 1,211,000 | 4% |

| 8 : Transport and storage (inc postal) (H) | 60 | 2% | 1,455,000 | 5% |

| 5 : Motor trades (Part G) | 30 | 1% | 573,000 | 2% |

| 11 : Financial and insurance (K) | 20 | 1% | 1,031,000 | 3% |

| 15 : Public administration and defence (O) | 20 | 1% | 1,277,000 | 4% |

| 2 : Mining, quarrying and utilities (B,D and E) | 10 | 0% | 406,000 | 1% |

| 1 : Agriculture, forestry and fishing (A) | 0 | 0% | 490,000 | 2% |

| Column Total | 3,975 | 100% | 30,815,000 | 100% |

In Bakewell, development is constrained by 3 distinct designated areas: The Development Boundary, the Central Shopping Area and the Conservation Area. The majority of units within Bakewell are independent stores, but there are also quite a few national operators located within the town such as Rohan, Costa, Boots, Co-op, Holland and Barrett and now Aldi [4:1].

# Development in the National Park

Between June 2008 and December 2019, the Peak District National Park Authority made 8,605 planning decisions. There was a higher overall approval rate for planning applications within the Peak District National Park (87%) than for England overall (86%). During this time, the Peak District National Park Authority also had a higher approval rating (86%) for major development applications when compared nationally (82%), although there have been relatively few major development applications (48) in the Peak District between 2008-2019 [5].

Despite national parks covering more than 9% of land in England, the main industries remain agriculture and tourism-based employment in the Peak District. Development management in national parks, which ‘have the highest status of protection in relation to landscape and scenic beauty’ [6], is conservation-led, rather than market-led. And many businesses within the National Park derive direct and indirect economic benefits from their unique location and relationship with its landscapes. It is this relationship that future development in the National Park seeks to foster and build upon to enhance the landscape in the Peak District [7].

The current evidence demonstrates that [8], although national parks in England account for only a small proportion of the overall regional and national economy, protected landscapes support substantial levels of economic activity and perform relatively well against key economic indicators such as rates of employment and self-employment. However, their overall productivity is often below that of the wider economy, particularly because of the greater prominence of relatively low value industries such as tourism and land management, and the under-representation of high gross value added sectors such as financial services found in urban towns and cities. There is much less difference, however, when compared with other (non-designated) rural areas.

# Business premises and employment land

The Employment Land Review 2008 [9] report outlined 15.94ha employment land within the Peak District National Park with a further 5ha of land predicted to be needed by 2026 (equating to 3.5ha of industrial space and 1.5ha of office space).

Between 2008 and 2019, there was an average of 32 applications per annum relating to a use class of A or B in the Peak District.

Use Class A & B Full Planning Permission & Change of Use PDNPA Planning Database

# Minerals and extraction

Mineral extraction has been part of the Peak District economy for centuries; it continues to provide jobs and revenue for the area, although the number of local people working in the industry was less than 2% in 2001. In 2019-2020 there were 26 active surface quarries in the Peak District National Park, covering almost 900 hectares, ranging from large limestone quarries such as Old Moor (part of the larger Tunstead Quarry complex) or Ballidon Quarry, near Parwich, down to small-scale building stone quarries such as Bretton Moor, north of Foolow, or Wattscliffe Quarry, near Alport.

Around three quarters of those are actively extracting material to varying degrees, while the remaining sites are subject to ongoing restoration or aftercare obligations following completion of mineral extraction. Additionally, there are two mineral waste disposal sites covering 36.3 hectares, and an underground fluorspar mine, the permission boundary of which is large (2,182 hectares) but where permitted extraction is confined to a linear band covering approximately 40 hectares.

The principal sources of Carboniferous limestones, which are worked in Derbyshire and the Peak District National Park are found mainly in an area which stretches from Buxton, in a south easterly direction through the southern half of the National Park, towards the Matlock and Wirksworth/Cromford area. As a result, Derbyshire and the Peak District is one of the largest producers of aggregate grade crushed rock in the country. Crushed rock for aggregate is supplied overwhelmingly from the Carboniferous limestone.

Over the coming years, some internal shifts in the local labour market are expected to arise from the current Peak District National Park planning policy. It is considered likely that current policies will result in some displacement of extraction activities from the National Park to areas in the remaining parts of Derbyshire. This is not anticipated to have a significant impact on overall local workforce numbers over the coming years [6:1].

Minerals extraction activities in the High Peak and Derbyshire Dales areas is therefore a resource of national significance, contributing around 7% towards the national supply of minerals annually. An assessment of the area’s ‘landbank’ has found ample reserves that could provide vital resources for years to come [6:2].

Without the aggregate resource from the two districts in the wider Peak District, the viability of major capital development projects across the Midlands and Northern regions would be compromised. High transport costs mean that there is an inherent need for local aggregate resource [6:3].

# Farming and land management

Farming and land management are not just important for economic output, they are essential to shaping the look of the National Park, for example field patterns, miles of dry stone walls, local buildings, grassland and moorland. On which all other industries like tourism depend.

The latest employment figures show at least one in every 10 jobs in the Peak District is in farming. In 2016, the DEFRA census showed there were 3,064 individuals employed in the farming industry. This is approximately 16% of the total estimated people in employment in the Peak District.

Despite agriculture being the predominant land use (124,863 hectares or 87% of the Peak District), all of this land is classed as a ‘Less Favoured Area’ for farming. For Less Favoured Areas (LFA), average farm income fell by 42% to £15,500 between 2017/18 and 2018/19. This highlights the economic difficulty in farming in upland areas like the Peak District and highlights the importance of farming subsidies to the sector.

Public investment in farming is essential for the economic sustainability of many National Park farms and is not counted in the wider economic ONS analysis. Basic Payment Scheme and agri-environment agreement payments equate to over 90% of farm business income for LFA grazing livestock farms on average and 70% for lowland grazing livestock farms. The Basic Payment Scheme alone brings approximately £20 million a year to Peak District farmers and land managers.

Farming has always responded to the economy of the day and continues to do so. Some farmers are diversifying their businesses, for example by providing tourist accommodation and meeting the growing market for locally-produced food and drink. Click for further information on land management.

# Tourism

Tourism helps people to understand and enjoy the special qualities of the National Park. It is also a major contributor to the local economy. The Peak District saw visitor volumes hit a record high in 2018, with 13.43 million visitor days recorded representing a 13% growth in visitor days since 2009. Tourism expenditure also reached record levels, with £677 million generated from tourism in 2018, representing a real term growth of 13% since 2009. As tourism is a fluid sector within the economy, it is difficult to compare it against a single sector such as manufacturing, as tourism contributes directly and indirectly to many sectors.

Further to this, Peak District tourism businesses have the advantage of the Peak District being an iconic consumer brand, having a rich range of natural and cultural heritage and public pride in the destination. A strong visitor economy is important to the economic health of the area. Visitor spend provides employment, offers business opportunities and helps sustain local services. Click for information on the visitor economy.

# House prices

As of May 2020, the average house price in the UK was £235,673 [10]. Of the main three districts within the Peak District, High Peak and Staffordshire Moorlands had average house prices significantly below the UK average, whereas Derbyshire Dales was significantly above the average. However, further data is needed before we can look at average house prices for the Peak District, as the data in the table is an average for the entire district rather than just the area that is within the National Park boundary. Within the National Park, we would expect to see much higher average house prices.

UK House Price Index by District May 2020

| District | Average House Price |

|---|---|

| High Peak | £195,290 |

| Derbyshire Dales | £297,538 |

| Staffordshire Moorlands | £190,337 |

# Workforce commuting

The Peak District provides a valuable source of skilled and highly qualified workers for businesses outside the National Park boundary, as well as providing attractive places for workers to live or visit. It has a higher proportion of residents employed in professional and senior managerial positions (36.6%) than the national average (28.4%) [11].

The 2011 Census recorded 19,099 workers aged 16–74 living in the Peak District National Park and 17,835 people aged 16–74 working within the Park.

Of the 19,099 resident workers, 56% work within the National Park (including those who work at or from home), 28% commute to the districts intersected by the National Park and the remaining 16% work elsewhere in the UK, offshore or abroad. Of the 17,835 people working in the National Park, 60% also live in the Park, with 28% coming from the districts intersected by the National Park.

# Broadband

Nationally, 31% of small businesses reported that poor broadband or mobile coverage was a barrier to growth, while 26% said it had caused them to lose business or sales. In rural areas like the Peak District, 39% of small businesses received download speeds of 10Mbps or less. The same proportion (39%) consider their broadband speeds insufficient for their current business needs, rising to 46% when considering future business needs [9:1].

Broadband can help traditionally rural industries like agriculture expand or diversify, as well providing access to new markets. Nationally, in 2018, 96% of farmers had access to the internet, with 89% of these stating that broadband was an essential tool for their business. However, only 16% of farmers reported receiving superfast broadband speeds in 2018, although this was up from 9% in 2017. A significant 42% of farmers had speeds of just 2Mbps or under, although this is also improving, down from 50% the previous year [12].

Regional partnerships to facilitate the roll-out of broadband across local authority areas are present across the Peak District National Park and the wider Peak District. Superfast Staffordshire covers the Staffordshire Moorlands area of the National Park. Currently, just 82% of commercial premises across the area have access to superfast broadband, although Superfast Staffordshire aims to achieve 96% coverage by the end of 2020 [13].

Digital Derbyshire covers the Derbyshire Dales and High Peak regions of the National Park. Their aim is for 98% of businesses able to access speeds of at least 24Mbps by the end of 2020 [14].

# Mobile phone connection

Mobile connectivity is vital for businesses, especially small firms. Yet patchy coverage and poor voice connectivity can hinder performance and productivity, with 57% of small rural businesses nationally experiencing unreliable voice connectivity. 59% of small businesses in rural areas like the Peak District also experience unreliable data connectivity [9:2].

Poor mobile connectivity can be a particular barrier for rural agricultural firms and traditional farming businesses, which account for almost a third of all business units across the Peak District. Nationally, 97% of farmers owned a mobile phone in 2018, but only 17% reported a reliable mobile signal in all outdoor locations and only 19% in all indoor locations [12:1].

# Covid-19

There is a delay in the availability of much of the data we rely on to assess the economy of our market towns and the rural economy in the Peak District. This means that we can't yet fully see the impact that Covid-19 has had.

However, we can say with certainty that our market towns and retail spaces are heavily reliant on independent shops and use classes focussed towards supporting tourism as well as residents of the Peak District. And we can see that, between March and early June 2020 [15], travel into the Peak District was far below our usual trend due to the national lockdown. Therefore, many of the businesses that rely on footfall rather than online or manufacturing will have been economically hit the hardest.

Rural tourism accounts for around 80% of domestic tourism and recent VisitBritain estimates suggest it will see its revenues fall by £17.6bn this year as a result of Covid-19 control measures. This is almost a third more than the estimated impact of Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) on tourism in 2001, after inflation.

Other relevant factors include a population distribution (including among those who are defined as economically active) skewed to older people, when compared to urban areas. Older people are more likely to require critical care and/or die as a result of Covid-19. It follows that self-isolating and shielding behaviour will also disproportionally impact rural areas. Home working could also be more difficult in rural areas due to poor broadband quality and availability [16].

Nationally, the food supply chain in agriculture, horticulture, food processing and retail has continued to function in the period of lockdown. Some local food networks have flourished, but there has been real hardship among those businesses that served the food service market, especially the dairy sector [17], which could have bigger implications for the Peak District.

What are the gaps in our research & data?

- Re-starting the economy in rural areas: What has been the impact of Covid-19 on tourism, agriculture and the market towns?

- True value of farming and land management: Estimating the value of agriculture, forestry and land management in protected landscapes is challenging. IDBR figures are generally underestimates, as significant numbers of farming and forestry businesses are not registered for VAT and/or PAYE and therefore excluded from the IDBR. How do the benefits of land management support other sectors like tourism?

- Natural capital mapping and value: What is the natural capital value of the Peak District and how does this support the UK economy?

- Peak District Business Survey: Many businesses in the Peak District are not reflected in national data. The last survey was undertaken in 2005 and shows a large gap in our understanding of SMEs and other businesses in the National Park.

PDNPA LDF: https://www.peakdistrict.gov.uk/planning/policies-and-guides ↩︎ ↩︎

DDDC: https://www.derbyshiredales.gov.uk/services-business/economic-plans-partnerships/peak-district-partnership ↩︎

DDDC: https://www.derbyshiredales.gov.uk/images/Bakewell_case_study.pdf ↩︎

PDNPA: https://www.peakdistrict.gov.uk/__data/./img/pdf_file/0022/72472/Bakewell-Employment-Land-Review-Final-Report-May-2016-.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎

GOV.UK: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/planning-applications-statistics#2019 ↩︎

High Peak: https://www.highpeak.gov.uk/media/2674/Minerals--Aggregate-Extraction-in-High-Peak--Derbyshire-Dales---Draft-Report/pdf/Minerals___Aggregate_Extraction_in_High_Peak___Derbyshire_Dales_-_Draft_Report.pdf?m=1514474274637 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

National Parks England: https://landscapesforlife.org.uk/application/files/9315/5552/1970/Economic-Contribution-of-Protected-Landscapes-Final-Report-2 ↩︎

PDNPA Employment Land Review: https://www.peakdistrict.gov.uk/__data/./img/pdf_file/0026/46673/employment-land-review-2008.pdf ↩︎

FSB: https://www.fsb.org.uk/resource-report/lost-connection-how-poor-broadband-and-mobile-connectivity-hinders-small-firms.html ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

GOV.UK: https://landregistry.data.gov.uk/app/ukhpi ↩︎

ONS: 2011 Census: Occupation, national parks in England and Wales ↩︎

Superfast Staffordshire: https://www.superfaststaffordshire.co.uk ↩︎

Digital Derbyshire: https://www.digitalderbyshire.org.uk ↩︎

PDNPA: Traffic Counter Analysis ↩︎

NCL.ac.uk: https://www.ncl.ac.uk/media/wwwnclacuk/centreforruraleconomy/files/researchreports/CRE-briefing-Covid19-and-rural-economies.pdf ↩︎

CLA: https://www.cla.org.uk/sites/default/files/CLA%20-%20Re-starting%20the%20rural%20economy.pdf ↩︎